The Financial Stability Implications of Each Possible Stablecoin Reserves Model

There's always something

Because various stablecoins have tried different models—and the stablecoin bills keep iterating—it’s perhaps worth quickly finding our financial stability center on each possible stablecoin reserves model that has existed or been proposed. Since financial stability has often been a talking point for proponents of each, the below lays out the risks of financial stability with each—and tries to be brief. In order of safety of assets:

Narrow banking

To truly be narrow banking, stablecoins must have reserve accounts at the Fed. Fed reserves are the only asset with no liquidity, credit, or duration risk. The financial stability risks here are well-known: Stablecoins would effectively become the safest banks in the world, incentivizing depositors—particularly those over the $250,000 FDIC insurance limit—to move their deposits to stablecoins, who would, in turn, place them at the Fed. This would disintermediate the banks and force the Fed to buy substantially more assets, or provide banks with substantially more funding directly.

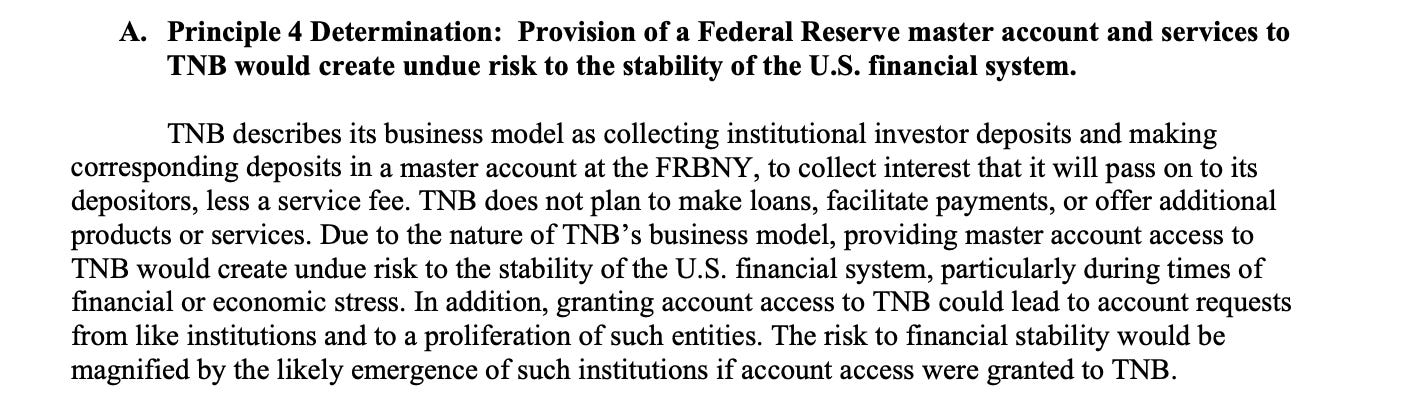

When the (attempted) upstart bank The Narrow Bank (TNB) tried to build a whole business around simply gathering deposits and placing them at the Fed, the New York Fed rejected its application for an account at the Fed on financial stability (and monetary policy) grounds. An excerpt from the rejection letter:

Master accounts remain a sensitive issue in the stablecoin/crypto debates, and the swing voters in Congress seem unlikely to allow master account access to even be tacitly allowed in potential stablecoin legislation.

Treasury bills

Ok, but what about direct ownership of Treasury bills; doesn’t that allow for effectively narrow banking without disintermediation? Some weird things can happen here.

One goofy, but probably less important, one: the debt ceiling. Short-term Treasuries set to mature around possible “X dates” can often sell off relative to Treasuries that bookend them on the yield curve. See, e.g., Circle reallocating in 2023:

More important: Much as the use of narrow banking would lead the Fed to need to do substantially more printing, material Treasury bill demand would strain the existing supply of Treasury bills. The Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee’s recent materials (p.11) explore stablecoin demand for Treasury bills going from the current $120+ billion to an estimated $1 trillion in 2028, citing Standard Chartered research. (That probably sounds high to most readers, but it’s worth exploring anyways since—in some sense—none of this matters if stablecoin market cap never grows that much.)

Shortages of Treasury bills relative to organic demand for such can lead the financial sector to manufacture private substitutes—which are prone to breaking down under financial stress. Prior to the financial crisis, the shortage of T-bills led the front end of the Treasury curve to price very richly, incentivizing both supply and demand of private-sector-manufactured AAA-rated short-term paper (ABCP, CP, repo, etc). From Stein, Hanson, and Stein (2016):

In present day, the hedge fund basis trade can be seen simply as one manifestation of the shortage of Treasury bills, as long-term Treasury debt is funded by hedge funds manufacturing T-bill substitutes—short-term, Treasury-backed repos—for short-term cash funds to invest in.

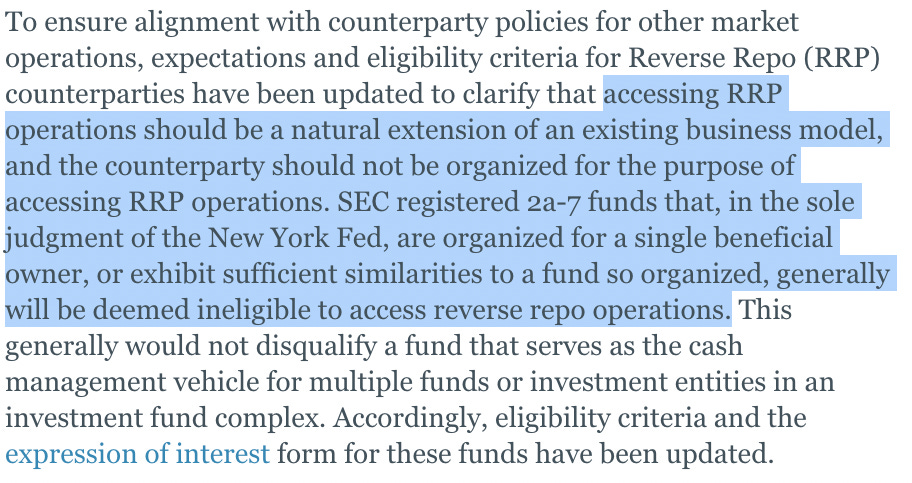

As Greenwood, Hanson, and Stein noted in their paper, the Fed’s overnight reverse repo facility (ON RRP)—which allows banks and money market funds to deposit funds overnight at a rate approximately equal to the monetary policy target rate—can help limit this dynamic by elastically providing money assets and putting a floor on the front of the curve. However, if unchecked, this would simply bring us back to the narrow banking world described in #1. Indeed, while the Fed ostensibly places a counterparty limit on the ON RRP, it continually raised that limit to accommodate its QE, to the limit’s current $160 billion. (For MMFs, this applies at the fund level; for instance, Fidelity had ≈$600 billion at the ON RRP in mid-2023.)

Yet, with respect to stablecoins specifically, the Fed updated its ON RRP counterparty policy in a somewhat subtle way that seems to prevent a stablecoin backdooring into a narrow bank at the ON RRP. While BlackRock specifically created a MMF—the Circle Reserve Fund, in which USDC is the only investor—to invest some of Circle’s USDC reserves beginning in November 2022, the New York Fed’s counterparty policy for the ON RRP added this bit in April 2023:

In other words: Hey Circle Reserve Fund, don’t even try.

If Treasury bill supply expanded dramatically, this would likely change the shape of the aggregate deposit franchise, but would not directly disintermediate on net, as the Treasury funds are spent into the economy as they normally would be. There’s some disintermediation in the sense of the shift in the curve of total demand for Treasury assets.

Treasury-backed repos

While short-term repos against long-term Treasuries likely don’t transfer much of the duration risk of long-term Treasuries to the stablecoin, some of it could remain—such as when 30-year bond prices fell by ≈8% in a week in March 2020 (particularly if stablecoin disclosure requirements are such that markets can see the collateral exposure).

The greater financial stability risk here is tying the supply of funding in money markets to crypto market cap. When cryptoasset market cap goes up, the supply of stablecoins needs to grow—and vice versa.

That means that when crypto assets fall, money market funding is at least rearranged. This is likely manageable in “normal” times for, though less so if the stablecoin market does indeed grow substantially. And certainly less so if it happens alongside a systemic event.

Bank deposits

“Deposits in insured depository institutions” is a common, unfortunate phrase, because it implies the institution is insured—rather than deposits up to $250,000. (Yes, in a systemic crisis, there are mechanisms by which larger amounts can be protected.)

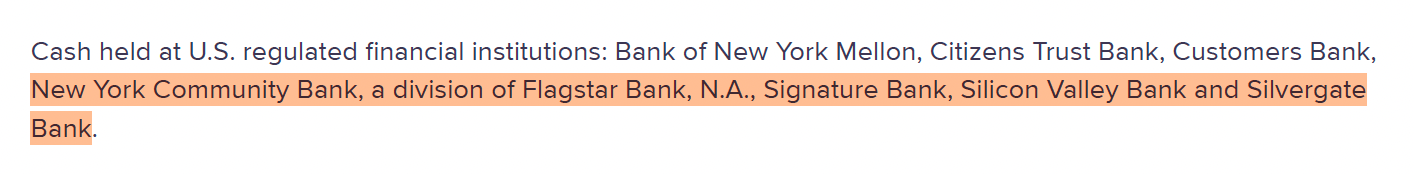

We saw the risks to the stablecoin itself of holding reserves in banks when USDC was trading at less than 90 cents on the dollar while SVB’s depositors’ fate was uncertain; when they were rescued, redeeming USDC still faced backlog delays. Circle’s monthly disclosures of USDC’s bank deposit partners prior to March 2023 is surreal in hindsight1 (my highlighting):

However, this dynamic only turns stablecoins into a financial stability risk if they grow tremendously, such as along the lines of the Standard Chartered estimates.

The greater financial stability risk here, even at current stablecoin market caps, is akin to that noted for Treasury-backed repos: the tying of senior financial system funding (deposits in this case) to crypto market cap. That it’s typically been mid-sized banks servicing crypto means stablecoin (and other crypto) deposits can represent a material part of the funding profile (and the market’s view of their business model)—again, particularly if the stablecoin market grows.

And, to the extent the stablecoin market grows by coming into its own as a retail payment product, stablecoins would be effectively gathering insured (stable) deposits and transforming them into flightier, uninsured deposits concentrated in the banks servicing these clients.

Other risky stuff

Bitcoin, commodities, foreign commercial paper, whatever. Ironically, this is the one with the least financial stability risk if the stablecoin market remains around its current size and with current transaction purposes, which are, so far, limited beyond participating in the crypto ecosystem. Risky assets forming the backing reserve has the least financial stability risk because stablecoin market cap can ebb and flow dramatically in this world and only affect the markets for risk assets, rather than systemically important funding markets.

If, however, nonbank stablecoins become a $1T+ market used for mainly real-economy transactions, then there’s financial stability risk in the holders losing any money, and you don’t want this risky stuff backing any par liabilities that aren’t issued by a regulated bank. Avoiding the risks in holding these kinds of assets has seemed to be Congress’s primary motivation since it began drafting stablecoin bills. (If stablecoins stay small, however, avoiding such assets is great (stablecoin) consumer protection but may actually be a net negative for financial stability proper.)

Comments welcome via email (steven.kelly@yale.edu) and Twitter (@StevenKelly49). View Without Warning in browser here.

Notably, Customers Bank was also likely under some stress—it borrowed over $4 billion from the discount window, approximately 20% of its balance sheet.