Can the Treasury Kill the Basis Trade?

(Gently, of course)

Prelude

The Treasury’s normally sleepy “quarterly refunding announcement” on November 1 of last year was beloved by markets. Fear over how much Treasury debt was likely to come on offer at the long end had contributed to huge run-up in long-term rates. Slightly surprising markets, the Treasury signaled on November 1 it would moderate its increase long-end issuance and was comfortable continuing to be slightly above its typically targeted range of 15%-20% of Treasury supply being in bills. The slight tilt towards the short-term end of the curve at least contributed to, if not got too much credit for, the subsequent fall in long-term yields and market rally. See, for example, this graphic from the WSJ:

Basis Loaded

Everyone’s talking about the basis trade again: the BIS, the BoE, the Fed (and Fed researchers), the Financial Stability Oversight Council (which is, uh, all the US regulators), the SEC, the New York Fed, and the Treasury.

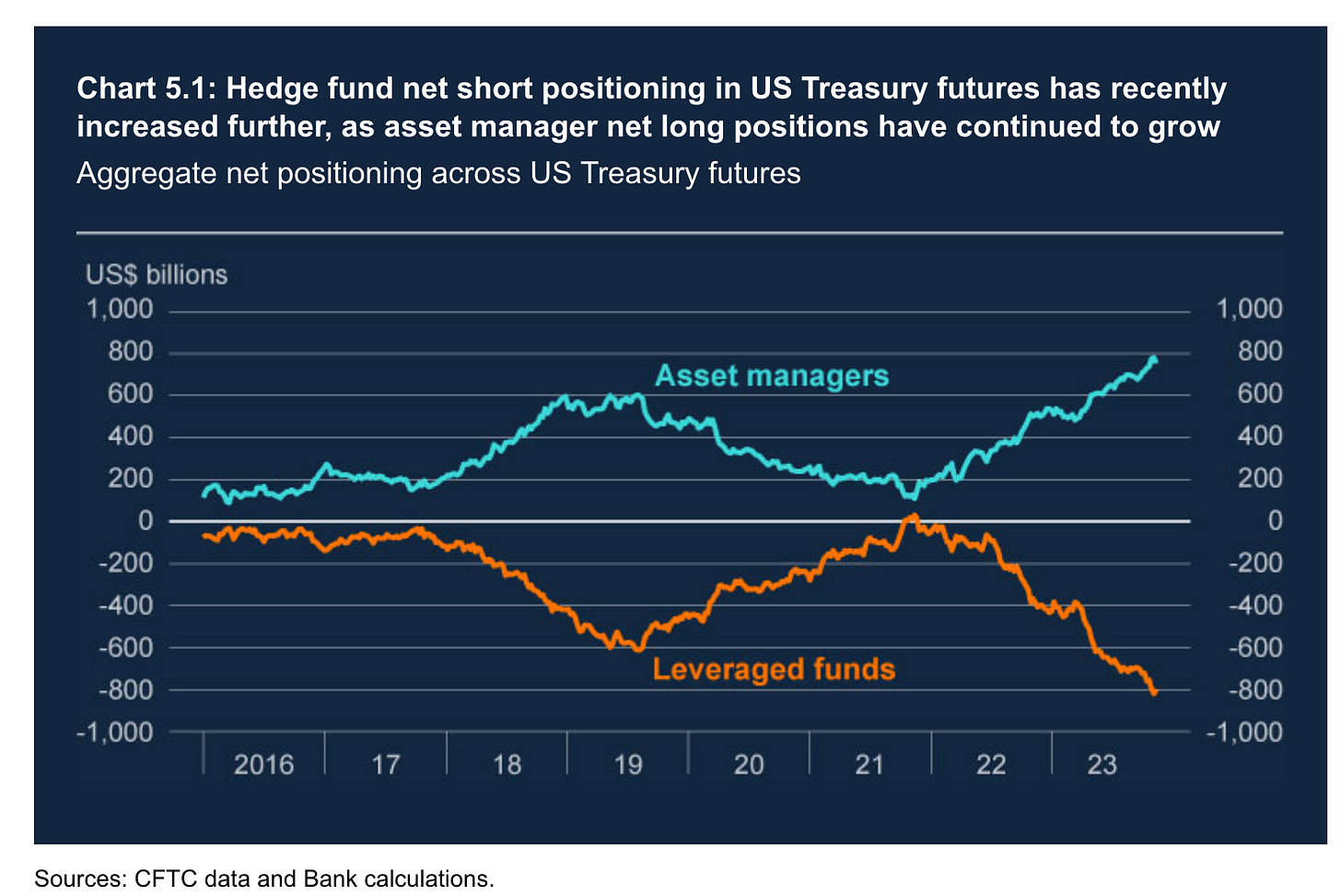

As readers know, the basis trade exploits the arbitrage spread between Treasury futures and the cash Treasuries that are “deliverable” into those futures contracts. A hedge fund (typically) performing the basis trade will go long the Treasury bond, and short the corresponding futures contract that is trading relatively richly. And, typically, asset managers take the other side of the futures:

The true size of the trade is unknown, but indicators like the above suggest it’s bigger than its pre-pandemic peak. The short position of “leveraged funds” (typically hedge funds) and the long position of “asset managers” (institutional investors like pension and mutual funds) have approached $800 billion.

Because delivering the Treasury itself upon expiry of the futures contract satisfies the hedge fund’s obligations under the contract, the hedge fund is, well, hedged. It’s free to collect that spread—“basis”—and then deliver the cash asset when the futures contract expires.

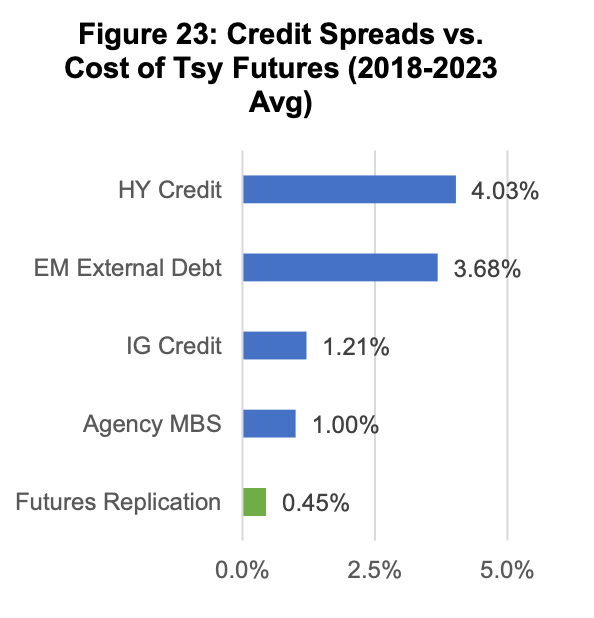

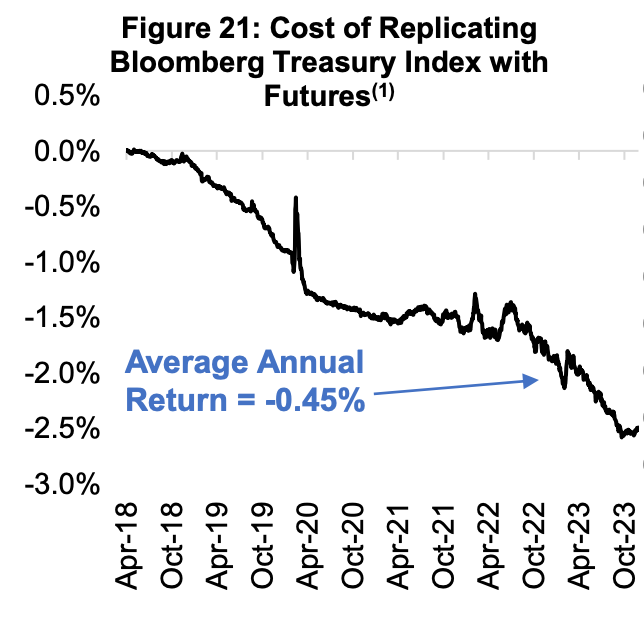

A recent presentation of the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC)—comprised of market participants that advise the Treasury on its borrowing plans and other Treasury market and economic issues—conservatively estimated about 45 bps of annual carry in this trade from 2018 through 2023:

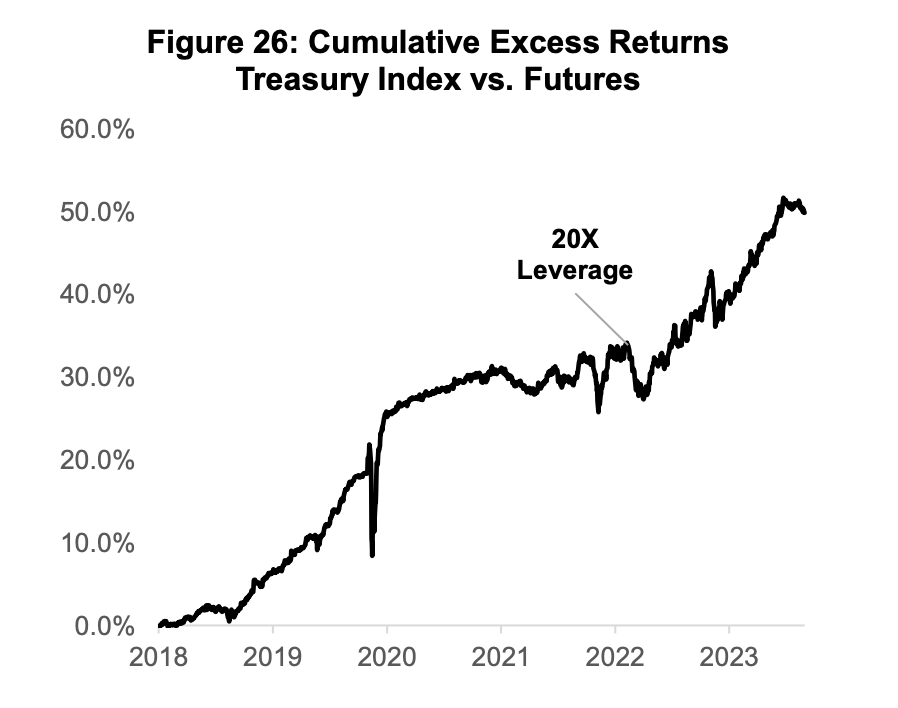

As the TBAC presentation noted, a hedge fund using 20x leverage—which the presentation calls “anecdotally…a good approximation” of leverage in the basis trade—can generate 900+ bps of annual excess return with this seemingly risk-free trade:

(Mind you, the 45 bps estimate from the TBAC presentation was conservative, and a recent Fed note put average hedge fund Treasury repo leverage at 56x.)

Basis Clearing

As readers remember from the start of the covid crisis, the trade isn’t actually risk-free; it can break down before expiry if price moves are severe and margin calls can’t be met without fire sales. This is a particularly acute risk when, as we saw in March 2020, there is a “dash for cash” and the basis diverges: At the outset of the pandemic, rates were headed lower for longer so futures prices rose, but Treasuries nonetheless sold off as investors sought money.

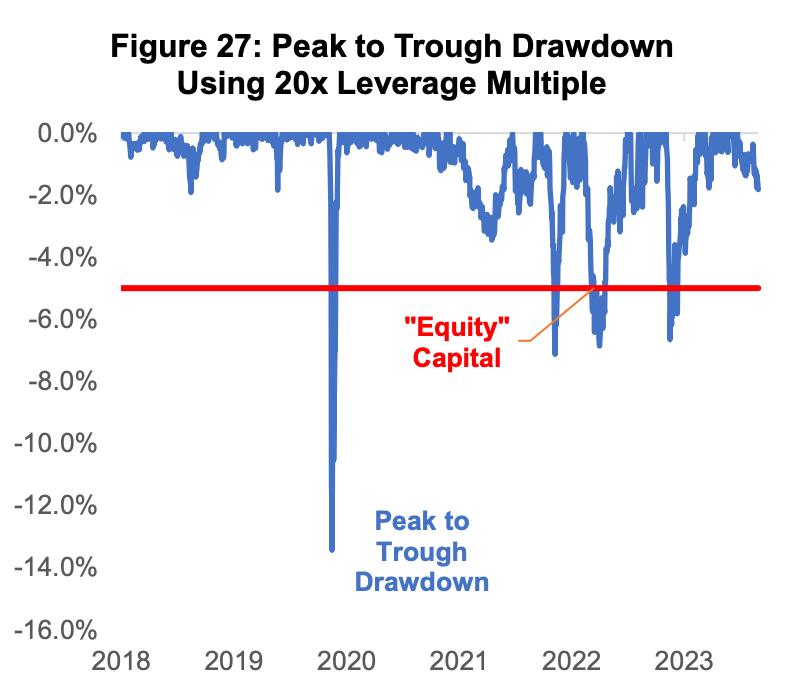

As the recent TBAC presentation showed, even with just 20x leverage, the basis trader’s margin was quickly blown through—exacerbating the dash for cash as hedge funds were forced to sell assets and close positions:

Stolen Basis

The hedgies running this trade might tell us they’re providing a public good because the UST demand from the basis trade improves liquidity and lowers the US cost of financing. Fact check: True. At least statically true anyways; dynamically, we have to consider the costs/risks of the basis trade implosion, but it’s reasonable to expect that, arithmetically, the average cost of financing might be lower (holding the Treasury’s average issuance maturity constant, that is…).

But this trade, funded as it is in the repo market,1 tells the Treasury something else: There’s a ton of structural demand at the short end of the issuance curve. All else equal, the funders of Treasury repo would likely be happier with Treasury bills—no counterparty risk, no collateral price risk, no legal/operational risk with respect taking possession of collateral. (i.e., better money.)

Thus, in addition to providing demand to the Treasury’s long-end issuances, the basis traders are creating a money asset (short-term, Treasury repo) from a long-term asset, helping satisfy institutional money demand on the short end. The Treasury itself is thus missing an opportunity, the size of which can (at least) be proxied by the basis trade, to issue substantially more bills with limited market indigestion—and without the need to rely on the basis trade machine. Indeed, it would crowd out the trade.

And Asset Managers Kick Rocks?

But would short-circuiting the repo/basis loop mean the asset managers on the other side of hedge funds’ futures short are just eating the costs of their futures counterparties disappearing? It looks unlikely.

The recent TBAC presentation to the Treasury on the basis trade analyzed asset managers’ motivations to use so many long Treasury futures. What the TBAC found is that active fixed income managers are stuck benchmarking to aggregate bond market indexes, which have increasing amounts of Treasuries in them.

These active managers, meanwhile, prefer to pick up their extra yield by higher credit concentrations—which, for various reasons (pp. 17-23), have tended towards having lower duration contributions than the index’s Treasuries they’re supplanting. To avoid this leading them to have a duration basis relative to their benchmark, they enter into long Treasury futures.2 Effectively, the asset managers are paying the 45 bps of carry to the hedge funds in exchange for the opportunity to invest in their preferred credit assets without worrying about straying from their benchmark on duration risk—a trade they can easily pick up yield on:

The TBAC presentation shows that as bond market benchmark indexes flood with Treasuries, asset managers tend to just pick up this duration exposure with Treasury futures, rather than reallocating their portfolio away from their lower-duration-risk credit investments:

So, to the extent the Treasury shifts its issuance toward bills, aggregate bond indexes will also have a shorter duration. Thus, bond funds will find that active credit management (which tends toward lower duration contributions) won’t leave the funds short duration relative to the aggregate bond market index—and thus they won’t have such high demand for long futures. (This also means the funds would be free of the implicit leverage in futures contracts!)

Making Money

There is insatiable demand at the short end that the Treasury has seemed unwilling to satisfy. Prior to the GFC, this demand was met with private sector replacements like commercial paper, ABCP, and repo—which of course proved to be poor substitutes. Deficits (and the Fed’s reverse repo facility) have helped solve that problem since, and long-term-Treasury-backed repo is a step safer than MBS-backed repo. But, even Treasury-backed repo trades unwind in crisis when institutions want to move up the moneyness scale.

Treasury prides itself that its debt issuances of the various tenors are “regular and predictable,” so any shift towards a shorter term structure would have to be managed carefully. Though, notably, issuance already shifts shorter during crisis episodes and other shocks, indicative of the limited price elasticity at the short end.

Too, it’d be remiss to not note that the only terming out of debt the Treasury has done in the last 20 years has been at times the Fed was doing QE:

The Treasury was thus offsetting to an extent the Fed’s efforts to pull duration from the market; the Fed’s subsequent unwindings of QE was followed by growth in the basis trade.

And yes, the Treasury aims for its debt issuance patterns to minimize the total cost of borrowing over time. Despite there being much less price sensitivity to front-end supply (particularly given the reallocation potential from Treasury repo to direct bill purchases), the extent to which the Treasury misses out on instances of a negative term premium on longer-term debt implies a theoretical—if likely nominal—cost. The tradeoff here, though, is less Treasury market blowup risk.

The Treasury can also be much less fearful of “rollover risk,” the typical concern about short-term debt, given it issues the world’s safest (and money-est) asset, and practically no one is constrained from buying short-end bills—unlike long-end bonds which may require the machinations of the basis trade.3 As noted, short-term debt already functions as the Treasury’s “shock absorber” exactly because of the market’s ability to absorb short-end supply.

Big Shorten

Financial engineering can provide substantial value, but, in the case of the basis trade, the Treasury doesn’t actually need its help. The market’s demand for institutional money assets exceeds what the Treasury has been issuing. Treasury can skip over the risk-creating basis machinations and issue directly to the ultimate funds-provider for the basis trade: short-term money market investors.

The acclaim Treasury got for its November refunding announcement can be just the beginning.

Related: Refitting the Standing Repo Facility to backstop Treasury trades like the basis trade

Comments also welcome via email (steven.kelly@yale.edu) and Twitter (@StevenKelly49). View Without Warning in browser here.

This note has slightly to say about the prime-brokerage-funded version of this trade. To the extent the Treasury shifts issuance toward the short end, though, there’d be less carry to harvest in the (prime-brokerage-funded) basis trade.

A Fed note estimated that hedge funds alone had $553 billion of repo borrowing collateralized by Treasuries as of December 2022.

They could also equivalently pick up this duration by repo-funding purchases of long-term Treasuries. There are various administrative reasons, discussed in the TBAC presentation, they prefer futures. Regardless, if they repo-funded long-term purchases, we’re back at the maturity transformation the hedge funds are currently performing, which gets us back to: the Treasury should just issue more bills.

The debt ceiling remains an issue for all Treasury debt, but increasing the quantum of short-term (i.e., regularly maturing) debt could potentially elevate the risk. Yet, the market tends to only worry about the couple days around the debt ceiling itself and only marginally; moreover, it’s not clear that issuance strategy should be driven by assumptions of default, that the Treasury should be playing into the historical accident that is the debt ceiling.

This is excellent, Steven, thanks. You highlight index replication needs, which rise when Treasury issuance rises, but there is also a endogenous demand for dollar assets. This would suggest the high yields currently offered by the Treasury short-end conflict with that demand. In the 2000s, we argued about a 'Savings Glut'. With ONRRP and T.Bill rates so high, perhaps we should start talking about a Return Glut for those savings, especially as it is clear other central banks cannot sustain high rates.

Thoughtful piece but there are several inaccuracies/misunderstandings.

The first issue is the overlooked error contained in Figure 27 of the recent TBAC report. The figure implies that drawdowns associated with a 20x levered basis trade would have exceeded the equity capital/margin of hedge funds on multiple occasions since 2018 and to a striking degree during the COVID pandemic. However, TBAC’s figure misconstrues the relationship between equity capital and basis trade drawdowns. The key error is that while returns to an unlevered trade that exceed 5% would indeed wipeout equity capital of a 20x levered trade (5% * 20x = 100%), the chart shows returns to the LEVERED trade. This is made clear by the fact that in Figure 21 the unlevered return in COVID is ~0.75% which corresponds to the levered trade drawdown in Figure 27 of ~15% (20 * 0.75% = 15%). The implication is that the levered equity capital drawdown 15% is very well short of a blowup! Either the chart should show a redline at -5% on and returns on an unlevered trade or a redline at -100% of the levered trade, but not a mix of the two!

The second issue pertains to this statement “But this trade, funded as it is in the repo market,1 tells the Treasury something else: There’s a ton of structural demand at the short end of the issuance curve.” The reasoning is backwards here. The basis trade returns are derived from the funding need required by asset managers long futures position. The demand for treasury futures creates a discrepancy between funding rates attainable in the repo market and implied funding rates on Treasury futures. The fact that hedge funds are able to obtain funding to extract the difference in funding costs does not imply that there is structural demand for short dated assets. In fact, the opposite takeaway could be true. Were Treasury to issue more bills, they may in fact “crowd out” repo funding supply and thereby exacerbate the dislocation between cash and futures. Said another way, the richness of short dated assets is largely irrelevant for basis trade returns. What matters is the relative richness of short-dated assets to implied funding. The presence of demand for the basis trade only indicates the existence of a positive funding/implied funding spread.

I also disagree with the conclusion that more issuance at the short-end will tend to reduce asset managers positions in treasury futures. As discussed at length in the TBAC presentation, index replication is only one source of demand for treasury futures. An additional source of demand is from the procurement of leverage afforded by futures contracts. For example, a common practice in pension investment schemes includes the purchase of futures to match liability duration with the left over cash being used to obtain equity exposure. Its precisely the levered component of futures that makes them attractive to asset managers!

All of this is not to say that there aren’t simple reforms that could be made. The fact that some mutual funds will purchase more costly treasury futures instead of repo-funding cash treasuries as a result of the treatment of repo in expense ratios is one example of a silly inefficiency that harms investors and does no meaningful good. That said, the overall thrust of this post needs to be reworked. If the target is to improve market resiliency of the treasury market by reducing the scale of the basis trade, the appropriate target should be the asset managers not the hedge funds.