Improving the Standing Repo Facility

Preparing for a future "dash for cash"

Fed officials have made clear their resolve to tighten financial conditions until they see significant progress on the inflation prints. Tightening financial conditions, another balance sheet runoff, and generally elevated financial instability have renewed questions over exactly how helpful a tool the Standing Repo Facility—which did not exist in “standing” form during the last tightening cycle—will be for limiting future financial disruptions.

The SRF can help replace fragile/scarce funding, but it is of little help on the asset side…

A Helpful Tool

The Fed of course wants the SRF to help prevent the likes of the repo blowup of 2019. As FRBNY’s Lorie Logan put it in March:

However, should pressures in overnight markets unexpectedly emerge, the new Standing Repo Facility (SRF) that the Committee established last year is also available, providing an important backstop to support effective policy implementation and smooth market functioning.

On top of this, however, the Fed and market participants are also well aware that liquidity in the Treasury market is already strained as the Fed forges ahead. From the minutes of the Fed’s early May meeting:

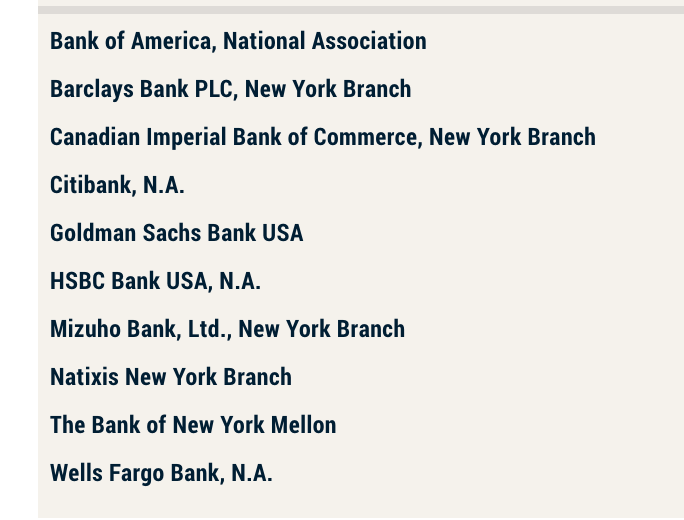

The standing repo facility continues to be available at the upper rate of the fed funds range (2.5% as of last week) for up to $500 billion (and “the aggregate operation limit can be temporarily increased at the discretion of the Chair”). The facility is available to the 25 primary dealers and the following banks (so far):

Not a Panacea

Even the SRF’s biggest fans would likely acknowledge that the SRF is not a panacea to Treasury market volatility and intermediation challenges—as is often the case with with lending facilities. Sometimes you just need some capital to come in and add to net balance sheet capacity. This is a role the Fed can easily play as it has no capital requirements, and can thus act as though it has infinite capital.

During the repo stresses of September 2019, the Fed was mostly able to calm the market in the short-term with repo interventions. But, with concerns ever-present that the lending facilities wouldn’t be sufficient to keep the market in check, particularly around year-end, the Fed began expanding its balance sheet again in October 2019.

At the onset of COVID, despite the Fed offering up to $500 billion of repo backstop every morning and afternoon, plus some more billions of term repos, it still had to hoover up Treasuries to restore market order. For instance, in less than two full trading weeks, the Fed bought over $500 billion of Treasuries—from March 23 to March 31, 2020.

In 2022, we’re seeing Treasury volatility pick up and liquidity get strained, but the Standing Repo Facility, which came into its “standing” status existence in July 2021 (the above instances were ad hoc interventions), has hovered around zero (occasionally registering at $1 million):

Because the SRF is a lending facility with just 35 counterparties (some of which are part of the same parent companies), any need for its liquidity provision outside of these counterparties requires them to use their (finite) balance sheet space and pass along the liquidity.

On that constraint alone, the SRF is not a panacea. There is still a backstop role for the Fed, and it’s still worth considering the other ideas out there—central clearing, cross-margining, SLR recalibration, etc.

Shortcomings Remain

But, let’s assume a situation in which balance sheet capacity is there and hasn’t reached its limits. After all, repo facilities were helpful in 2019 in and 2020! Broadly, there are four levels at which a market participant holding a Treasury might find a standing repo facility useful.

The treasury holder’s repo (or other) funding refuses to roll. All else equal.

Easy! Enter: the SRF. Substitutes perfectly.

The repo funding rolls, but with a higher rate and/or haircut. All else equal.

The holder may bear the cost higher capital needed for the haircut or the higher interest cost, or it may replace the funding with the SRF—which prices at the upper limit of the fed funds rate at a slight haircut (consistent with normal market practice).

SRF can work well again here!

The repo funding rolls, but the Treasury market overall is experiencing a dash for cash—so the market price of the Treasury (and thus the amount funded from the repo lender) is lower.

The SRF doesn’t do any better here! It also lends against the market price of the treasury (subject to the usual slight haircut).

As structured, it’s not necessarily supposed to do any better. The SRF is really focused on repo rates. However, monetary policy implementation—especially during times of financial instability—involves influencing the whole range of interest rates, particularly the treasury yield curve. And in this situation outlined above, there is a massive disconnect along the curve.

Same situation as above, but the haircut is higher due to higher Treasury volatility/illiquidity.

Here, the SRF gets you part of the way—it buffers against the higher haircut. But, after that, you’re back to #3.

Thus, that the Fed lends at the fed funds upper limit doesn’t necessarily do any good for improving the implementation of monetary policy. Yes, it helps keep the direct repo rates around the policy rate, but if the 10-year treasury being funded at that repo rate has just blown out several percentage points in a day, there’s still funding stress; the security can no longer simply be repoed to repay the previous repo. And now the yield curve is several points off what would be consistent with what the Fed would consider effective monetary policy implementation. And it may have to ramp up its purchases.

C’est La Vie?

Maybe. But! To the extent these cash treasuries were held in economically hedged positions, the participants getting blown out are those who were effectively the marginal liquidity provider to treasuries—and thus, the marginal monetary policy implementer. It might be policy-optimal to keep them in their positions.

In 2020, this was the hedge funds that had been doing cash-futures arbitrage en masse—in the event, they were long (providing liquidity to) off-the-run treasuries, and short the futures contracts into which they could deliver those treasuries. But, when the dash for cash stuck a wedge between bids on cash treasuries (which sold off) and the price of the corresponding futures contracts, which tracked expectations for lower policy rates, the liquidity demands on each leg of the trade moved the wrong way.

It was hedge funds in 2020, it could just as well have been bond funds, banks (remember when they all copied LTCM’s such trades?), etc. And at this time, the futures prices were doing the Fed’s work for it, rapidly moving rates lower; cash treasuries were working against the Fed by selling off.

Making the SRF more Market-Based

To the extent the Fed wishes to minimize disruptive private liquidations (of both long and short positions), and to the extent it wishes to minimize outright buying interventions and instead serve as more of a backstop, it should contemplate tweaking the SRF to make it more market-based. Instead of operating in the way of the old-fashioned discount window, which is better at replacing a run on a bank deposit liabilities than on its assets, the SRF should take more of a portfolio view. Lending against the matched position would allow the Fed to lend more into the Treasury market without a pursuant increase in risk.

The Fed has the authority and historical experience in dealing with derivatives, if in a very different context—the Bear Stearns rescue. Section 4(4) of the Federal Reserve Act allows the Fed to exercise “such incidental powers as shall be necessary to carry on the business of banking within the limitations prescribed by this Act.”

For instance, Section 4(4) is the authority the Fed uses to set up emergency lending SPVs. It was also the authority relied upon when the Fed and JP Morgan effectively took a market-based approach to Fed warding off $30 billion of Bear Stearns’s assets—in the newly created Maiden Lane facility to support the JPM rescue: the Fed took on related portfolio derivatives “incidentally” to its assumption of the cash securities.

The SRF should operate similarly in our increasingly market-based financial system and Treasury market. It should open itself up to matched positions. Lending against a hedged position would allow the Fed to more effectively implement monetary policy; it would help prevent a selloff of cash Treasuries—and all the knock-on selloffs—into a crisis/recession.

An SRF that reflected market-based portfolios and the real risk of dashes for cash (as opposed to just lost repo funding) would be able to lend more against a safer position. This would help limit liquidation of cash Treasuries and derivative positions (and balance sheet capital in the process) by the marginal implementers of monetary policy. And it would do so during crisis-time, when the returns to effective monetary policy are at their highest.

Comments are turned off here but more than welcome via email (steven.kelly@yale.edu) and Twitter (@StevenKelly49).