Does Private Credit Really Reduce Systemic Risk?

If you squint

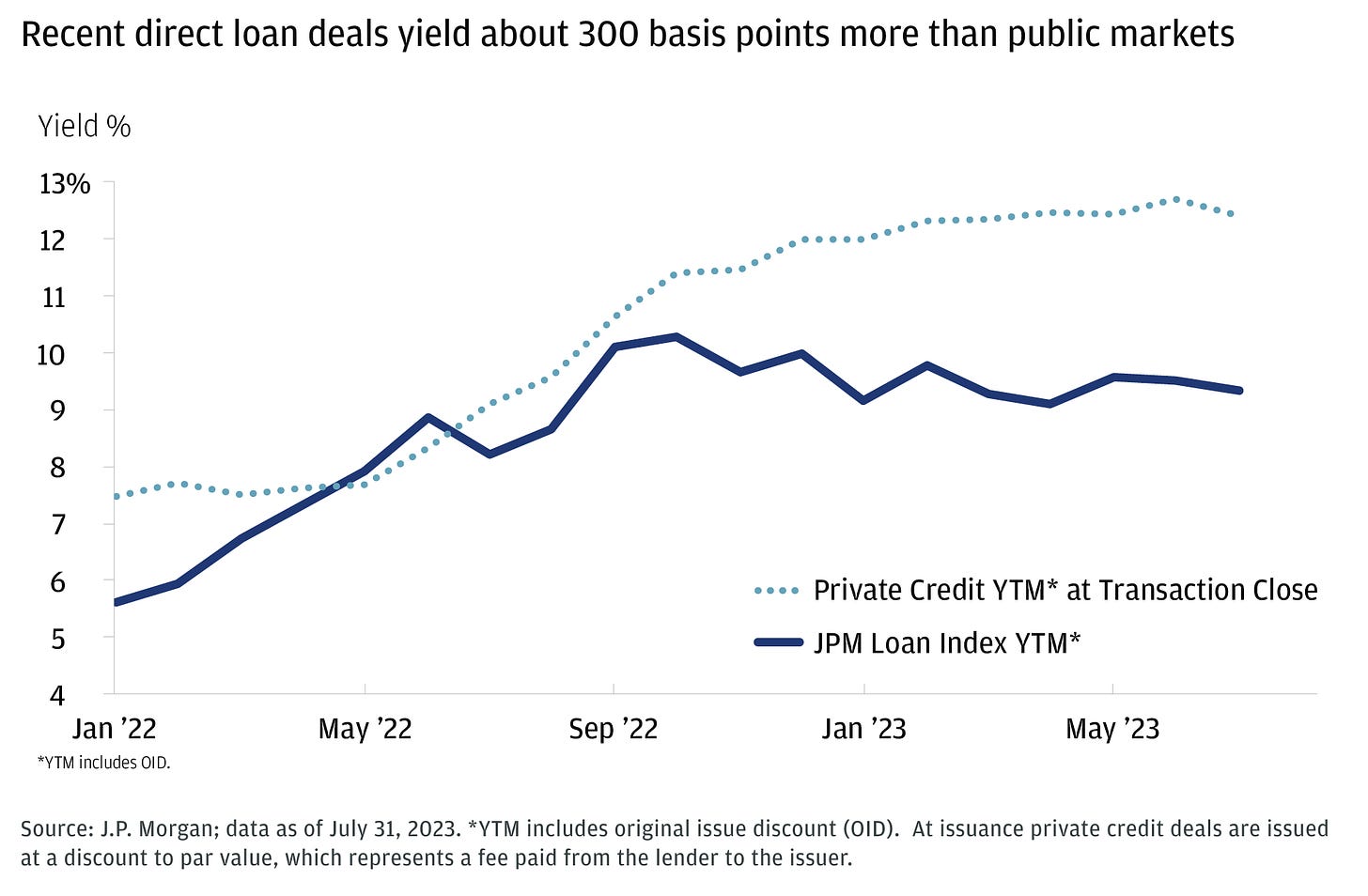

The trend towards private credit (PC) has shown that there is a market-clearing price where those shut out of other borrowing channels can entice investors that are willing to give up liquidity for a couple hundred basis points.

Private credit tends to be relatively duration-matched. Its investors face long lock-up periods. On its surface, this looks like a net stabilizing trend. It’s essentially bank loans without the fickle deposit funding, right? Just ask Apollo CEO Marc Rowan:

“Every dollar, every euro that moves off of a regulated bank balance sheet de-risks the system. […] Everything on a bank balance sheet is levered 10 to 12 times. When you move it to a mutual fund, it gets zero leverage. When you move it to an institutional client, it gets zero leverage. When you move it to a BDC, it gets 1.5 times leverage. And so on and so on and so on. So, every time you move something out of a banking system, you de-lever the system.”

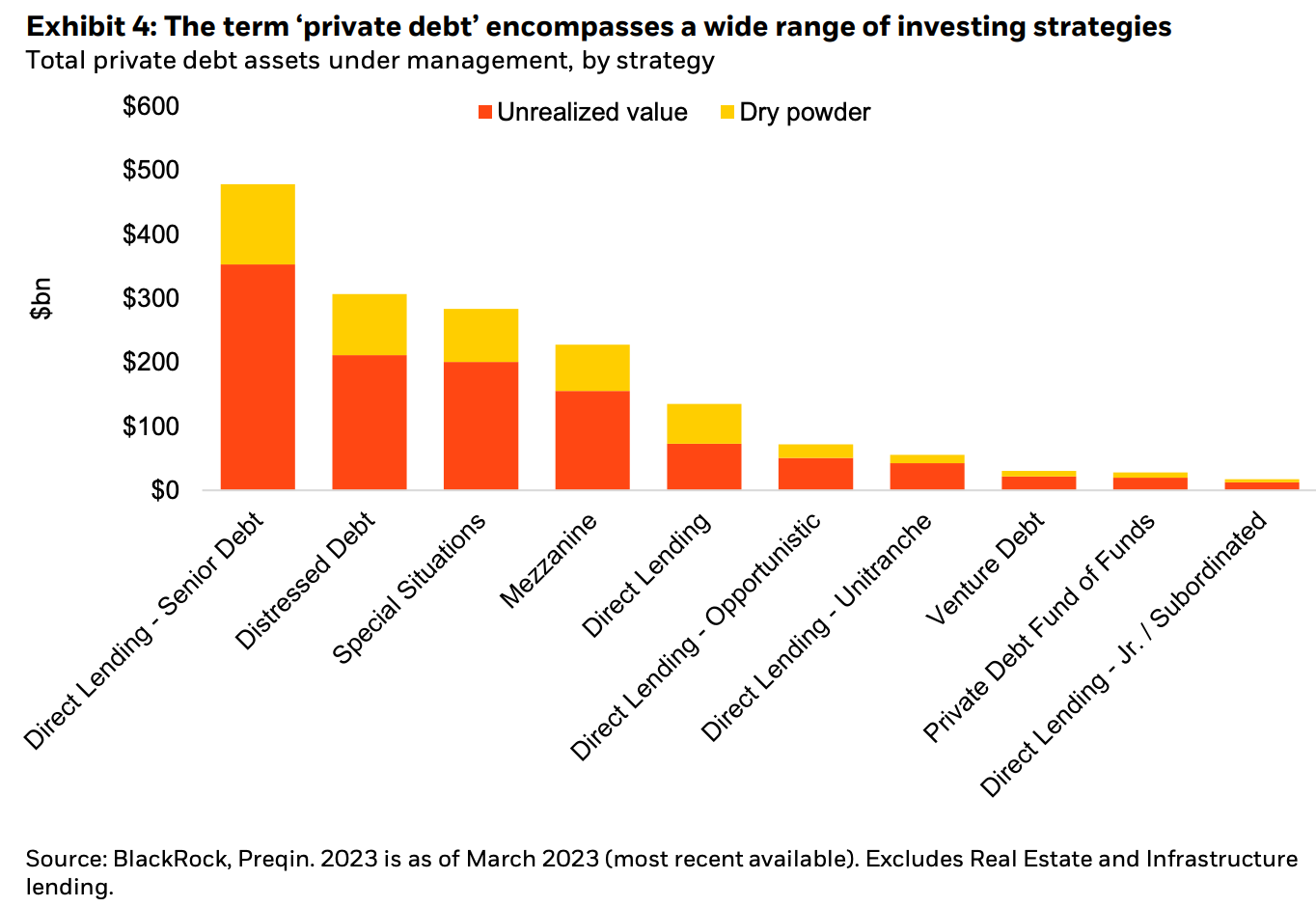

Ok, so, is the growth of private credit—now at about $1.6 trillion and projected to approximately double by 2028—a free lunch? At least systemic-risk-wise?

Three-Card Money

It’s worth following the money to unpack this. Accepting as given that PC is indeed offering a premium and limited correlation to public markets—all with low leverage— what’s really happening as money “moves into” this space?

For one, nothing is being “de-levered” on a quantity basis. To follow the story of Apollo’s Rowan, moving a dollar into private credit actually moves the dollar from the investor’s bank account to Apollo’s—and then to the end borrower’s. The banking system’s leverage is unchanged—albeit lower than if it had written the loan, so average leverage per loan is lower, so far. (The banking system, having lost out on making those loans will distribute more earnings to shareholders to avoid sitting on excess equity in the absence of new loans.) Never mind that PC isn’t necessarily in competition with banks on many of its loans—some just never would happen, some would go to banks, some would go to junk bonds, insurance companies, etc.

There may be some degree of increased banking stability, beyond banking system size implications, depending on what exactly is reallocating into private credit. For instance, a reallocation from junk bonds to private credit probably doesn’t do anything in either direction on systemic risk, and just moves money around the banking system. Alternatively, if a fund is being enticed to reallocate into PC from some holdings of excess deposits invested at money market rates, you are potentially operational-ifying the deposits. i.e., the liquidity that did belong to a financially-attentive fiduciary with a high deposit beta now belongs to a private credit borrower that holds the liquidity for operational (i.e., low beta) reasons. Again, there’s no leverage change here, but you end up with a more valuable aggregate deposit franchise.

Yet, there’s also the risk of the SVB problem here. When investors were allocating funds hand over fist to venture capital in 2021, this money wasn’t somehow leaving the banking system, it was ending up at Silicon Valley Bank and its kin—which banked the innovation economy. When the innovation economy hit recessionary conditions, it turned into a bleed of deposits that, when publicly revealed to be worse than expected, turned into a run.1 If you were to tranche the entire economy, the tech/venture world would be a very junior one—so you can see why interest rates’ path of destruction hit that pocket of the banking system first.

There doesn’t seem to be a First Bank of Private Credit Borrowers out there as PC’s borrowers tend to be more sector-diversified and credit-quality-diversified than the world of venture capital. Yet, of course, high-touch service and niche business understanding was SVB’s edge too, and that type of business model can tilt you toward more junior economic tranches with high economic betas; indeed, anecdotally there is some private credit tilt towards software and tech. And that tilt would be expected, given, as with SVB’s customers, PC is attracting borrowers whose needs are not being met by traditional banking.

Regardless, one can see the inherent limits to money moving to PC. Private credit lenders can only reallocate existing money; they can’t create money that banks and the Fed can. (If they moved to short-term funding, they could perhaps offer greater moneyness—such as offering repo to holders of uninsured deposits. But alas, that would be antithetical to private credit’s identity—although maybe increasingly less so.) That is, for every loan private credit makes, it gets closer to the kink on its funding curve, where sourcing additional investment pushes the cost of capital too high and squeezes the profit margin to zero—based on the quantity of liquidity alone! Some portion of existing liquidity has inelastic demand (and an even greater portion has insufficiently elastic demand); it simply won’t move into private credit at all or at a price that works for the end borrower. There are limits to deleveraging when “leverage” is actually the system’s deposits (and the like). We need those.

Retrenching Banks Retranche

However, that’s not to say private credit can’t absorb an infinite amount of capital risk. (Subject of course to representations made in their offering docs, etc etc.) Private credit has no regulatory capital requirements and seems to have advantages with respect to high-touch lending, bespoke arrangements, credit workouts, and the like (advantages that, when acknowledged by the market, can allow PC to use less capital than in the alternative). Banks are often less-equipped to do these things for various reasons, and/or it’s not their best use of resources.2 Plus, they face regulatory capital requirements.

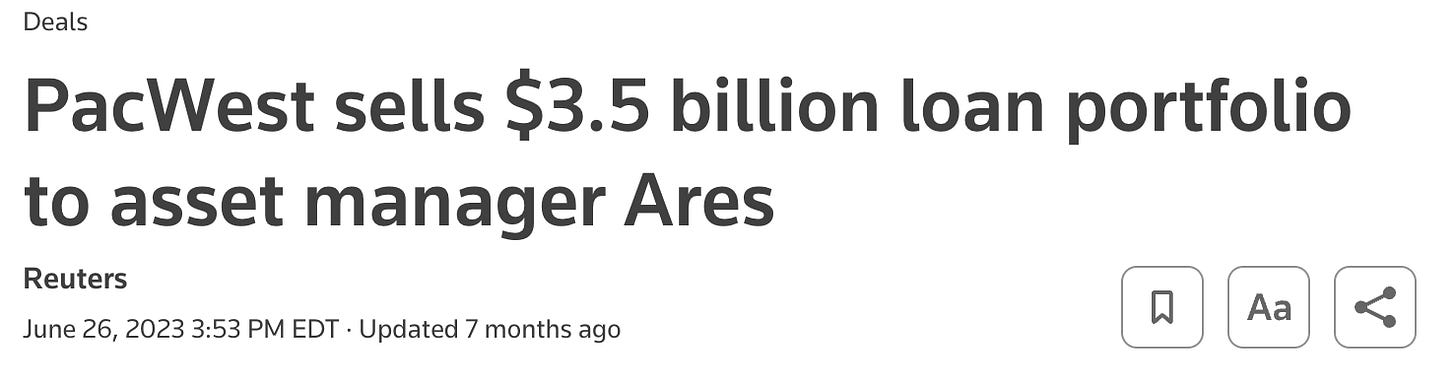

Banks, particularly regionals, have also been facing heightened scrutiny from markets (and supervisors) over their liquidity—and how it might interact with the capital risks in their portfolio. In addition to the direct interest rate repricings the banking system has borne since the Fed started its rapid rate-hiking campaign, sharp and steep rate increases can quickly become credit risks. Hence, the market has been putting banks’ portfolios of CRE, auto loans, etc. under the microscope, and banks have been looking to offload those portfolios in many cases. And often to PC funds:

And while investors have been rushing into private credit, PC funds using leverage has also grown in popularity. While various forms of portfolio financing have recently boomed primarily in private equity, the trend has bled over into private credit funds.

Imagine a bank sells a $1 billion portfolio of high-maintenance CRE loans to a household name private credit fund, and simultaneously funds the purchase by lending the PC fund $1 billion. The bank has reduced its capital requirement without changing the size of its balance sheet, and the PC fund has grown its balance sheet without attracting new funds. And this isn’t just an illustration; there’s already been some deals with financing chains that were actually this short. In the deal for PacWest’s assets shown above, private credit firm Ares got financing from Barclays. Even shorter: Bank of Montreal provided $6.4 billion of deal financing to a private credit group led by KKR that bought a $7.2 billion loan portfolio from Bank of Montreal.

But even without a direct chain this short, a private credit loan doesn’t change banking system leverage, as shown above. Private credit can siphon a particular loan and push on average leverage; it can’t siphon deposits.

And this isn’t just regulatory arbitrage; the bank’s balance sheet is, in practice, receiving additional protection from the private credit fund’s capital, potentially its collateral, and from its relative skill in, well, private credit. This is banks retranching their place in the economy. Retranching is just banks being good banks as: higher interest rates raise the credit risks and resource demands of various assets; depositors (particularly since last March) are relatively stir-crazy about what’s protecting them on banks’ asset side; and, of course, Basel Endgame.

Comments also welcome via email (steven.kelly@yale.edu) and Twitter (@StevenKelly49). View Without Warning in browser here.

I always love breaking out this Bagehot quote, which is a great way to describe how financial supply chains emerge and evolve:

Under every system of banking, … there will always be a class of persons who examine more carefully than busy bankers can the nature of different securities; and who, by attending only to one class, come to be particularly well acquainted with that class. And as these specially qualified dealers can for the most part lend much more than their own capital, they will always be ready to borrow largely from bankers and others, and to deposit the securities which they know to be good as a pledge for the loan.

- Walter Bagehot, Lombard Street, 1873

The side effect of these more “efficient” financial supply chains is complexity. Much like we saw with real supply chains during the pandemic, if the system breaks, complexity makes it much harder to get something (in the case of finance: funding) from point A to B. The same is true of financial daisy chains. Think about how difficult it was to restructure individual mortgages during the GFC. Or how challenging it can be for central banks to get money to the end-user they’re trying to target in a complex financial system.

To the extent one is worried about the next crisis being in private credit, the story probably has to be something about regulators losing sight of the risks in this more complex system. But, you can’t have a financial crisis without a breakdown in money liabilities, which private credit neither offers nor seems to implicate elsewhere (as in the case of venture capital and SVB). So, absent some other confounding crisis, it seems the concern behind “systemic risk is building in private credit” thesis would be “asset price go down”—which, of course, is no crisis.

Glad you wrote this. I've been meaning to write on Private Credit for a while and now I don't have too!

First observation would be that this seems like a natural development as more of "deposit" money is now uninsured. No real difference from bond market funding.

Second, I like Wigglesworth conclusion:

… private credit is too small and too little leveraged to cause major wider problems. When problems do arise, locked-up capital means that the pain is more contained. And if an investor does need to ditch a big private credit fund exposure, they can do so at a discount to another big institution.

Third, the place to watch is pretty much the same risks that hit the mortgage market during the GFC: "liquidity lines" from banks that are really credit guarantees, and additional leverage being added through derivatives. Market is still young, so hopefully not much of this yet.

Finally, Bloomberg had a nice piece on the link to insurers. Insurers are increasingly investors in this "private credit" space and are doing so through the Apollos, etc. Insurance accounting and capital rules (in the US) is a bit more forgiving than bank accounting and capital rules. This probably means a slower ultimate realization of any losses, less of a firesale externality risk.

I understand your arguments, but the analysis it's too static. There is just a brief mention of a dynamic state change e.g. the run on SVB where it from solvent to insolvent in few days, which is a pretty short time constant. Static analyses serve a purpose, but are insufficient to understand stability. Model the "money" flows via double entry bookkeeping's assets + liabilities = equity relationship. Professor Steve Keens free Minsky modeling software is the ideal simulator for economic modeling. It's downloadable from Sourceforge and you'll find videos on Youtube explaining the software and modeling various fundamental dynamic aspects of the economy.