The Macro Story of SVB Isn't Just About the Fed

SVB: if not them, then who?

In May’s House Financial Services hearing/grilling of failed bank executives, the interrogation lamp regularly hovered over the issue of the uninsured deposits, particularly SVB’s. Approximately 94% of SVB’s deposits were uninsured at end-2022, accounting about for about 78% of total liabilities (and higher if you adjust for the fact that SVB had at that point already started tapping the FHLB to replace lost deposits). Signature and First Republic weren’t far behind.

Naturally, this led to lots of angry questioning from Congress, like this particularly combative exchange between Representative David Scott (D-GA) and former SVB CEO Greg Becker:

Rep. Scott: “Who made the decision to maintain this reliance on uninsured deposits—given the warnings also by our federal regulators? Who made this decision, Mr. Becker? This foolish, irresponsible, and deceitful decision—who made it?”

SVB’s Becker: “Congressman, as I said, that’s been our business model for as long as I can remember-”

Rep. Scott (interrupting): “Who made the decision, my friend?! Was it you?!”

Throughout his testimonies, SVB’s Becker regularly responded to questions about SVB’s proportion of uninsured deposits as he did above: with some form of “that’s how SVB has always done it.” Which… is actually the start of a really good explanation—but it’s of course horrible by itself. The “why” of this business model wasn’t just some bad management decision, it’s a macroeconomic result. SVB has always done it that way because that’s what the macroeconomics having a large innovation sector called for.

Much of the uninsured deposits questions from Congress, as in the example above, almost seemed to suggest that SVB just greedily decided against renewing an FDIC insurance policy for the rest of its deposits. Even the Government Accountability Office picked up on this suggestive language, saying, “SVB and Signature Bank relied on uninsured deposits to support their rapid growth.” As has now been well publicized, supervisors had at least noted the resultant risks, but failed to pursuantly rein the banks in.

But if Silicon Valley Bank didn’t “rely on” uninsured deposits, or if supervisors simply killed the business model, Silicon Valley the place wouldn’t have gotten banked—and that’s a macro story.

Forward Misguidance

Part of Becker’s telling of events was already a macro one. The screenshot below is an excerpt from his testimony; he specifically calls out the Fed’s rapid shift in forward guidance as inflation proved problematic:

This part of the narrative was held (and projected) even more by much of the Republican bench: blaming the Fed and the Biden administration for excessive dovishness and stimulus. House Financial Services Chair McHenry said that what the three large failed banks had in common was that they “actually believed the bureaucrats.”

There are two threads here: one on assets and one on liabilities.

Assets

The assets side is that the Fed cut rates to zero in the pandemic and told the world they’d be low forever even as inflation started to roar. So, SVB loaded up on duration and got squeezed when inflation stuck around and the Fed reneged on its promise. There was also lots of congressional furor over the fact that SVB dropped its (very partial!) hedges against rising interest rates (and took profits) as the yield curve steepened. But society also relies on banks as a landing place for interest rate risk (because who else is gonna do it?). And doing so is also an essential part of how banks remain profitable. It also need not actually vary that much across rate environments; the profit stream is reasonably stable in the aggregate:

And banks hedging their rate risk is actually very uncommon. Some recent papers offer informative data here. From Lihong McPhail, Philipp Schnabl, and Bruce Tuckman:

After accounting for offsetting swap positions, the average bank has essentially no exposure to interest rate risk [from their swaps positions]: a 100-basis-point increase in rates increases the value of its swaps by 0.1% of equity. There is variation across banks, with some bank swap positions decreasing and some increasing with rates, but aggregating swap positions at the level of the banking system reveals that most swap exposures are offsetting. Therefore, as a description of prevailing practice, we conclude that swap positions are not economically signifcant in hedging the interest rate risk of bank assets.

And from Erica Jiang, Gregor Matvos, Tomasz Piskorski, and Amit Seru:

Interest rate swap use is concentrated among larger banks who hedge a small amount of their assets. Over three quarters of all reporting banks report no material use of interest rate swaps. Swap users represent about three quarters of all bank assets, but on average hedge only 4% of their assets and about one quarter of their securities. Only 6% of aggregate assets in the U.S. banking system are hedged by interest rate swaps.

The hedges that SVB dropped covered just 12% of its interest rate risk at end-2021, congressional brooding over their removal notwithstanding. This fell to just 0.4% at end-2022. (Plus, the 10Y-3M spread didn’t invert until late 2022. To the extent the 3-month rate is a good proxy for the price of wholesale funding that would replace deposits, SVB wasn’t really looking upside down even on a HTM basis until then.)

More importantly: if banks are stable, they are naturally hedged; the deposits continue to yield next to nothing while asset yields go up. You wouldn’t tell a corn producer to hedge its corn futures; it’s naturally hedged by its production output. Likewise is a bank hedged by its production output: deposits.

To extend the analogy, if a corn producer doesn’t tend to its field and ends up with an unmarketable product, its derivatives are now a huge financial risk: It has an unhedged futures exposure. If a bank doesn’t tend to its deposits sufficiently and they may end up much lower quality than expected, the bank similarly ends up with an unhedged asset exposure.

So, it’s only when the liabilities (and equity) side of the balance sheet gets destabilized that this asset accounting starts to really matter.

Liabilities

The liabilities side of the blame-the-Fed story is that the pandemic-responsive Fed kept rates too low and printed too much money for too long, inflating the amount of deposits in the system—only to pump the brakes and reverse course sharply:

The natural attrition in deposits is the particularly relevant story for SVB, as its clients’ deposit “inflows” were effectively just new rounds of equity funding—startups getting a new round from their backers and/or backers raising new funds themselves. If you tie the stability of short-term liabilities to the health of growth equity markets…well, you’ve written a very short story.

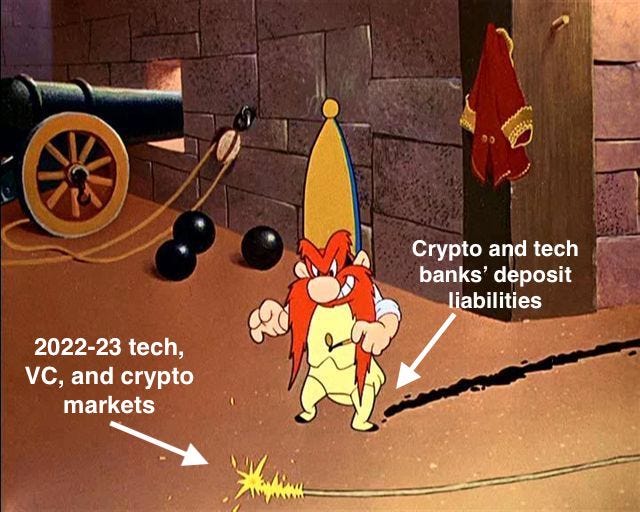

You can see how this worked for crypto banks too: A deterioration in the more-risky-than-equities crypto economy meant deposit attrition, less deposit inflow, less fiat inflow into stablecoins, etc. Again, you’ve tied deposits (the top of the liability stack) to the frothiest of asset markets (the bottom of the asset stack). It’s a structure quick to short-circuit.

Sure, banks take interest rate risks by having short-term liabilities and long-term assets. But, there’s a reason this evergreen truth broke down at the banks it did. Their interest rate risk wasn’t about the yields on their assets and liabilities—i.e., the prices. It was that the stability of their liabilities was ultimately dependent on very interest-rate sensitive sectors—i.e., the quantity of their liabilities had the built-in interest rate vulnerability.

What’s In a Name?

Ok, but with crypto the solution is easy: Just don’t let the banks be doing that. That’s more or less the direction the bank supervision has gone, without quite banning the activities. They’re now effectively highly discouraged.

Regardless, what about the SVBs of the world? Its whole value proposition was that it banked Silicon Valley. It built an understanding of the needs of the innovation economy over decades in a way that GSIBs never cared to or would. It provided high-touch service and a close relationship with its customers, all built on a strong understanding of their novel businesses and risky industry. But this closeness works both ways. Lending to high-risk startups means you need a strong understanding of their cash flows. SVB loans often involved “tying”—where a loan meant a customer also needed to keep its deposit relationship with the bank. Loans to investor funds often meant the startups that the funds invested in also had to bank with SVB. This is an understandable demand for visibility given the inherent risks in lending to the innovation economy. It also is a business model that means you end up with huge amounts of uninsured deposits—given the current structure of deposit insurance at least.

So, we can do what we’re kind of doing to crypto and basically just say: Ok, you had your fun. But a decision to destroy the niche that is Silicon Valley lending (or other similar regional or sectoral niches) seems much more macroeconomically consequential than killing bitcoin liquidity. That’s not to say, “What’s good for SVB is good for America.” But outright kicking the SVB model out of the system without something to replace it might just mean a material downtick in American innovation. That said, there’s probably a middle ground of killing some of the lending while the rest ends up being done by private equity, private credit, insurers, etc. But it’s something that merits careful consideration.

Broadly speaking: no regulatory or statutory change is needed for the SVB business model to work if it’s rolled up into a GSIB—just look at the relative prosperity of SVB UK in the hands of HSBC versus its US sibling in the hands of First Citizens (aka, “who?”).

The SVB model works great on the asset side, having a history of almost exclusively turning profits. First Republic similarly “experienced only $45 million in cumulative net loan losses after originating $241 billion in single-family residential loans” since its 1985 founding. But as we’ve seen, it’s not stable across environments on the liability side.

Yet, rolling up banks that are undiversified regionally or sectorally into the largest banks is not particularly popular in D.C.—catching only stray or mixed support from regulators, legislators, and the Biden admin. Ratcheting up deposit insurance seems to have a wide audience and certainly would be directionally helpful, at least with avoiding rapid runs at foundering banks. But the onus is then on the deposit insurance premium schedule and/or bank supervisors to be in the weeds of banks’ business models—such as when there’s an ACME fuse from risk asset markets to the upper tranches of the liability stack.

Comments welcome via email (steven.kelly@yale.edu) and Twitter (@StevenKelly49). View Without Warning in browser here or click below to share.