Misdiagnosing SVB

A run on banks, not a run on banking

SVB was way out over its skis on duration risk. And it dumbly dropped its hedges. It sustained some losses on its available-for-sale securities and massive unrealized losses on its held-to-maturity book.1

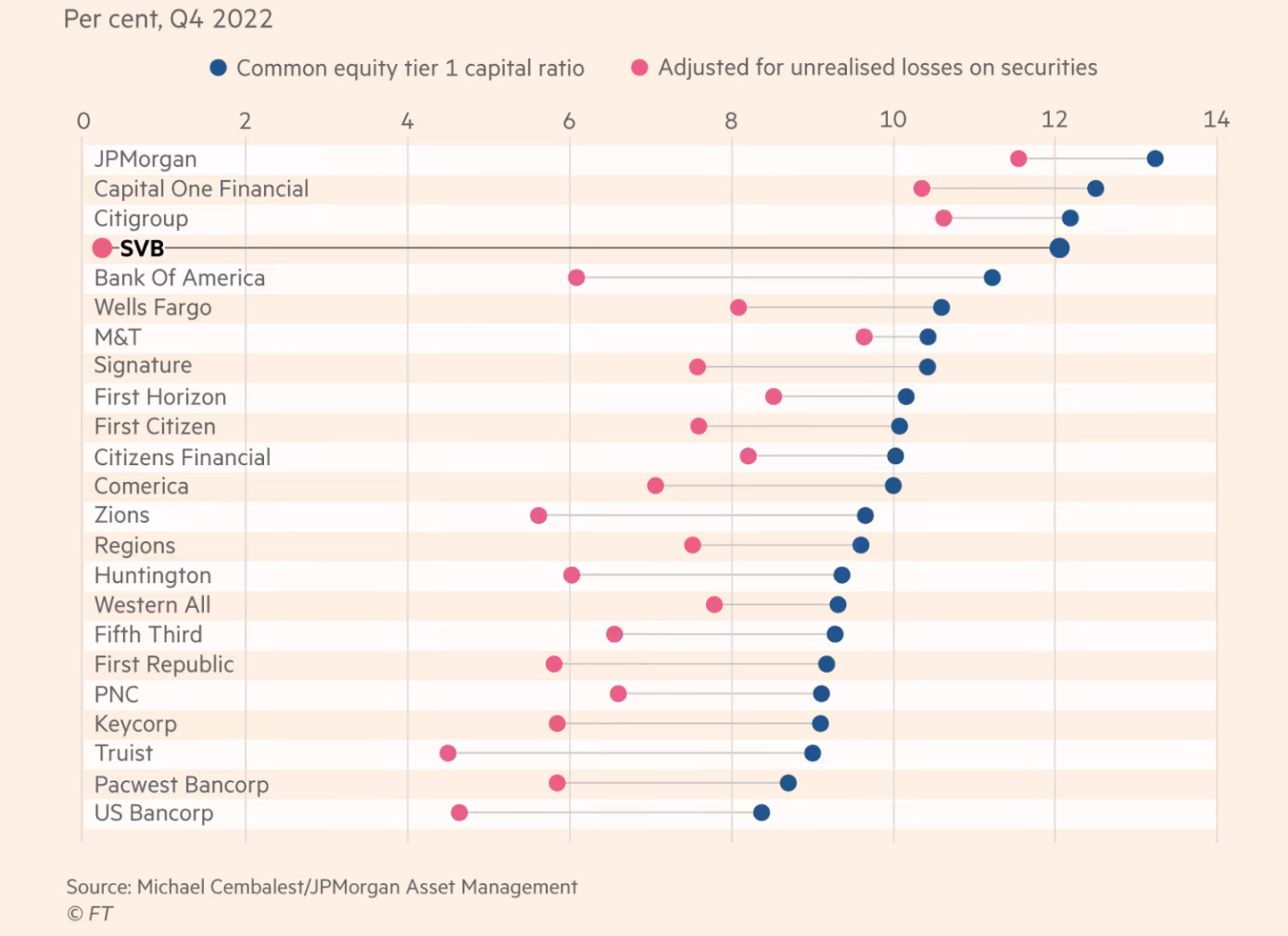

So, we get excellent charts like this, and the story of SVB’s downfall seems to be written:

Yet, unrealized losses aren’t untold losses. SVB filed a 10-K in February with a similarly excellent table showing it had $15 billion of losses on its $91 billion held-to-maturity portfolio at year-end. And SVB ended the month trading at $288 a share.

Bank runs do not start from information available in a 10-K. When a firm has to file an emergency 8-K, however, all bets are quite literally off.

The emergency fundraise and revelation that SVB’s all-in bet on tech/VC meant it was bleeding funding sparked a sudden interest in the unrealized losses. The revelation of the deposit burn made it clear that SVB’s business model of banking Silicon Valley was clearly becoming non/less-viable on a go-forward basis. This was a run on SVB’s business model.

And when a bank’s business model no longer looks viable, then it starts mattering what the bank looks like from a liquidation perspective. In general, a bank is always going to look horrible through that lens, and the balance sheet grinds to a halt. So much of a bank’s value is tied up in counterparty/depositor/borrower relationships, providing its balance sheet as a service, its employees, ongoing management of assets within that bank’s corporate structure, long-term viability, etc. Capital ratios measure capital to assets, but the market measures capital ratios against a firm’s business model.

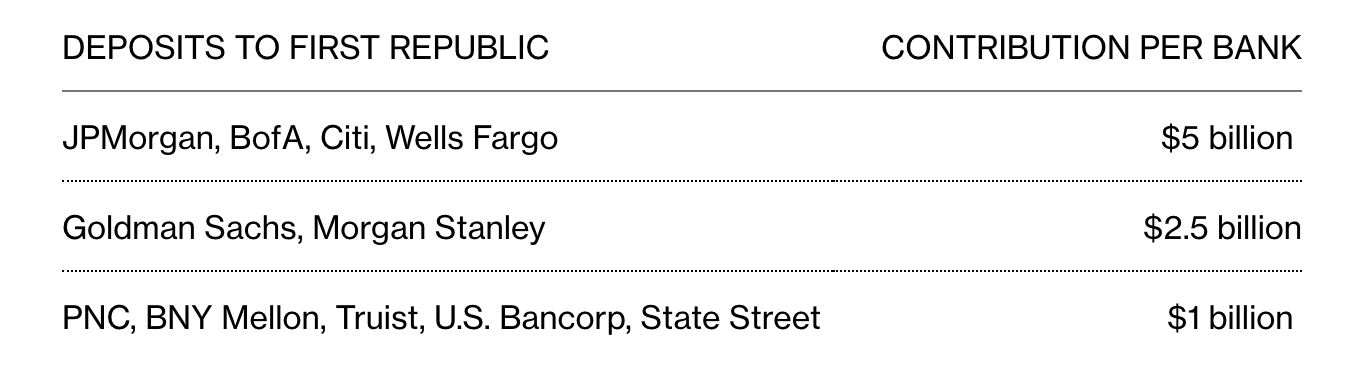

If, on top of that, you look accounting-insolvent like SVB, that’s…really bad. But, as mentioned, a run on the business model almost always makes a bank’s balance sheet look too weak. If we think the story is just unrealized bond losses, you could refer to the chart above to see who’s next. Looks like Truist and US Bank have the next lowest capital ratios after adjusting for unrealized securities losses. Yet, both have contributed to the big bank rescue effort of First Republic:

Hardly on death’s door. Instead, to the extent there’s been a run contagion from SVB, it’s been to banks with business models that look like SVB’s. The market has moved foremost onto First Republic and PacWest—both West Coast banks with similar businesses to SVB.

Here’s another chart on unrealized losses on securities in the banking system:

This chart is from a speech from FDIC Chairman Gruenberg…in February. He gave a similar one last quarter when, as shown above, held-to-maturity losses were even worse. Moreover, both charts above do not account for similar HTM losses on loans (which one rough estimate suggests than triples the amount of unrealized losses in the system). And when you’re talking about losses from changes in risk-free interest rates, it’s straightforward for the market to impute those losses on an ongoing basis.

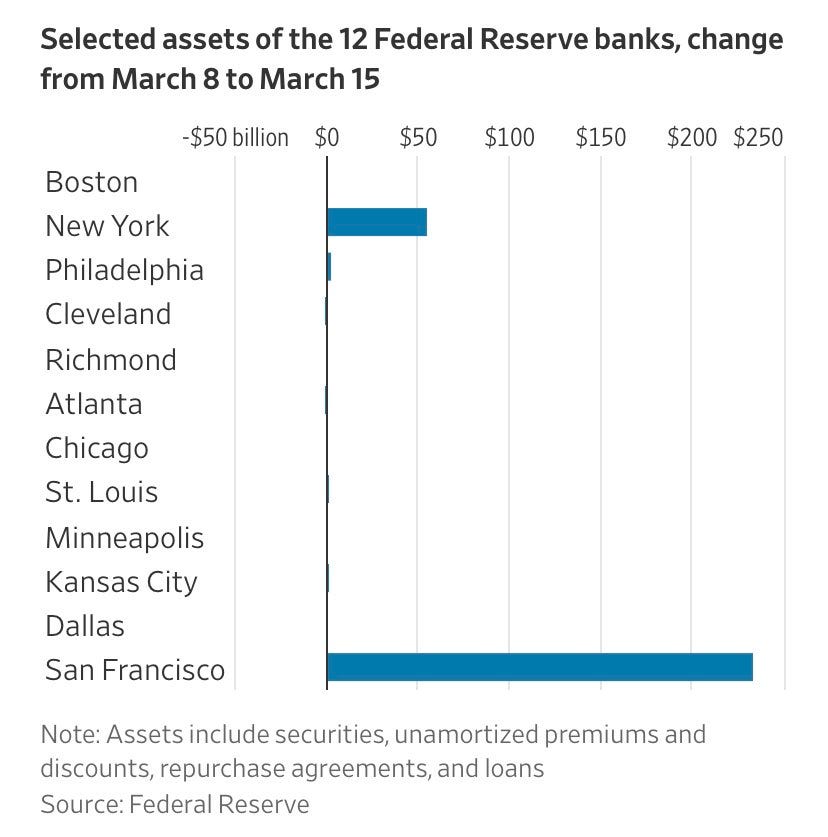

Despite all these unrealized losses plaguing the whole banking system, and despite banks confessing those losses to their shareholders, and despite the FDIC chair announcing those losses at a quarterly cadence to the world, we haven’t seen anything close to a systemwide run. The runs we’ve seen have instead targeted a particular banking business model. This isn’t a run on the Street. Large, diversified banks have seen inflows. It’s a run on the business model of catering to a highly cyclical industry (one that the Fed has eviscerated with its interest rate policy).2 Even the discount window activity surrounding SVB's failure told the story of the liquidity pinch being contained to the West, home of the tech sector:

This isn’t like a 2008, where you have toxic credit risk spread throughout the system and it’s not clear how bad it is or where it is. This isn’t a run on the business model of massive banks that no one could possibly buy or put into wind-down. This is the yield curve. It affects every asset the same way — and in a way that any intro finance student could ballpark.

That also means the Fed still has a credible nuclear option.

During covid and the GFC, rate cuts mattered for the macroeconomic recovery, but likely mattered little for financial contagion. When it came to containing and reversing the banking system stress and funding market blowouts, it took emergency authorities and exceptionally interventionist policies. In 2023, cutting rates 300 basis points would take all these held-to-maturity securities back to par and recapitalize the whole banking system. Not ideal from a monetary policy perspective, but it’s a quick and direct fix if it’s absolutely necessary—at which point it probably wouldn’t conflict with monetary policy anyways. No emergency authorities, myriad interventions, or Congress required.

Comments welcome via email (steven.kelly@yale.edu) and Twitter (@StevenKelly49). View Without Warning in browser here.

Oh and its executives did that dumb thing and someone wasted some money and that one person was greedy and that other person knew about that other thing the whole time, etc.

And remember, Signature Bank went down the same weekend for betting too much of the firm on catering to crypto clients. Same story.

Thanks, your comments on yield curve steepening as salvation are spot on - though cutting rates will be tricky with inflation clearly still unbeaten.

Steven,

This is EXCELLENT and describes better than any other analysis I have yet seen the nature of the challenges for banking, regulators, and of course the Fed.

I look forward to your future posts!

Cheers,

Ken