Where Was the Last Place You Saw the Deposits?

Some deposits got pulled, most just disappeared

Money can’t be nowhere.

What sounds like an annoying metaphysical philosophy can provide useful guardrails when examining monetary plumbing. While we obviously saw severe bank runs on a subset of banks in March, that money moved into larger banks.

This is worth reemphasizing because now the trillion-ish dollars of deposits that have disappeared since April 2022 are being increasingly characterized as customers “pulling funds” from the banking system—withdrawing their money over bank concerns or to chase higher yields. While these reallocations are indeed happening and can certainly cause deposits to disappear at a particular bank, they do not destroy aggregate deposits in themselves. Money can’t be nowhere.

[Warning: it’s a FRED episode.]

The deposits state of play

Total deposits peaked in April 2022 and bottomed in May 2023:

Switching banks or sending money to money market funds in search of higher yields does not reduce the aggregate amount of deposits in the system. It’s not as if MMFs don’t use banks and/or buy credit instruments from borrowers who don’t. Deposits can only be held in the banking system.

Going to the Mattresses?

Generally: an individual/firm/fund cannot “destroy” a deposit alone, unless they are stockpiling literal cash in shoeboxes. But cash in circulation has just dawdled along on its linear trend, rising less than $100 billion since April 2022:

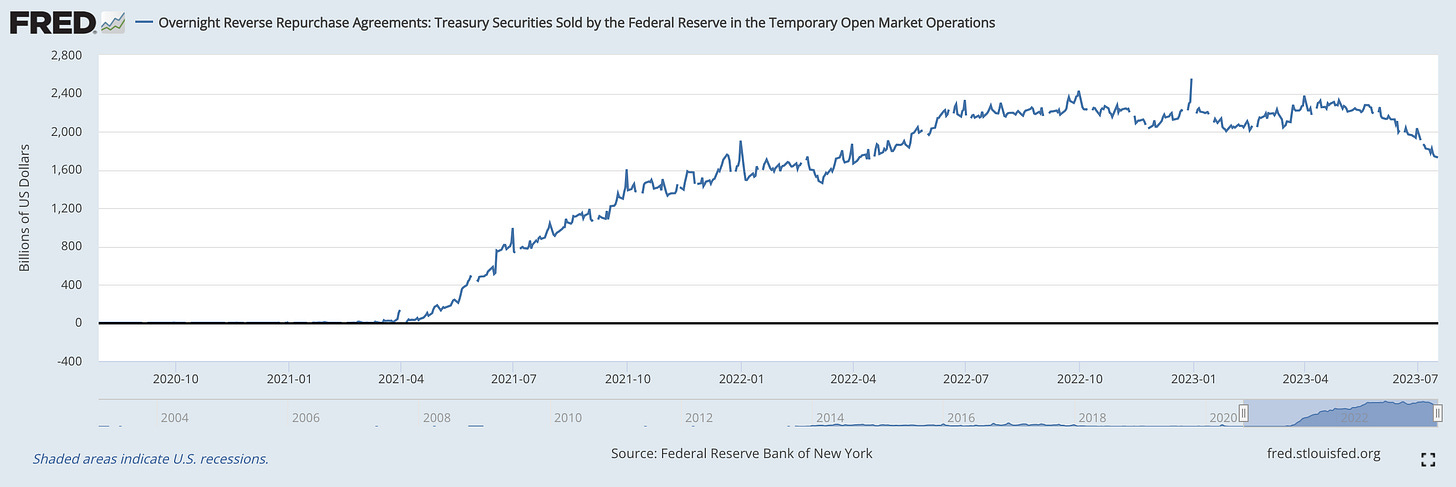

MMFs do now have something of a shoebox option, provided by the Fed: the overnight reverse repo facility. MMFs with access to the RRP facility can deposit funds overnight with the Fed—essentially taking the funds out of the banking system on a daily basis. The Fed sets limits on the size of this facility but has, in practice, continually raised the caps to accommodate demand for it.1

The RRP *did* continue trending upward for a few months after deposits started declining—increasing about $450 billion through June 2022, when the Fed began quantitative tightening and long before concerns about bank health—but has since leveled out. It did get a slight bump in March 2023, which likely indeed was the result of customers “pulling” deposits from the system.

The similar facility for foreign official account holders (think, e.g., foreign central banks’ dollar reserves) has increased about $100 billion since April 2022:

These—currency and Fed-run RRP facilities—are the main “stock” places deposits can actually disappear to. That is, these balances really can be the result of investors aiming to store/hold their money in those mediums. There are some other “flow” components that can affect deposit balances, mainly the Treasury General Account—Treasury’s deposit account at the Fed:

But individuals, firms, MMFs, etc. cannot “invest” in the TGA. They can’t withdraw funds from the banking system and put them in the TGA. They can invest in Treasury debt—causing deposits to temporarily fall as money flows into the TGA, but the Treasury is also continually spending its money and thus putting deposits back in the banking system.

The Treasury did recently refill its coffers, as you can see above, after the debt ceiling became no longer binding—to the tune of almost $500 billion. However, this was basically fully funded out of funds at the RRP facilities—aka, funds that were already non-deposits; note the recent decline in both RRP facilities shown above. Adding the TGA amount to both the RRPs’ totals, the TGA rebuild disappears, and the combined total is up only about $100 billion since we hit peak deposits:

Okay, so a net total of around $200 billion moving into currency and the deposit substitutes at the Fed. Where are the missing hundreds of billions?

Who Moved the Deposits?

The Fed ended QE and first raised interest rates in March 2022. (Its balance sheet technically peaked in… April 2022.) It officially began QT in June 2022.

Balance sheet reduction *mechanically* destroys deposits to the extent the securities sold by the Fed—or, in the case of maturing securities, are rolled over by the Treasury outside the Fed—go to buyers other than banks:

A nonbank buyer’s deposit account (the bank’s liability) falls by the purchase price, and their bank sends the payment of central bank reserves (the bank’s asset) to the Fed, which then destroys the reserves. In the case of the maturing securities in QT, the Treasury’s TGA balance falls as it pays them off, and the Fed destroys the received reserves.

Only if banks bought the newly sold securities would the deposits get replaced as banks funded the purchases by issuing new deposits.

But banks haven’t been bulking up on those securities. Banks' total amount of reserves at the Fed and QE-eligible securities has been falling since December 2021:

As referenced above, banks increase total deposits when they write loans and buy securities: the credit gets issued to a deposit account for the borrower. Conversely, when a loan gets paid off, that destroys the asset and an equal amount of deposits. Stable deposits would require new credit extension.

Banks' aggregate securities portfolio has shrunk, and loan totals have stalled:

This is suggestive of a natural deposit erosion from the asset side. Similarly suggestive is the breakdown between insured and uninsured deposits, at least as told by the clunky quarterly data through Q1-2023:

All the erosion is from uninsured deposits, with maybe a slight deceleration in insured deposit growth. Not exactly a rush of the average consumer’s deposits into MMFs—which would then either disappear altogether (if landing in the RRP) or show up as higher uninsured balances as the MMF invested them outside the Fed. Rather, we see a decline in what were likely mostly commercial deposits from sectors not getting new credit as monetary policy tightened.2

Comments welcome via email (steven.kelly@yale.edu) and Twitter (@StevenKelly49). View Without Warning in browser here or click below to share.

Postscript

Deposits as a share of total bank credit (loans + securities) shot up during the pandemic, from about 95% pre-pandemic to something like 110% in 2021. This ratio has since fallen back gradually, hovering around 100% and increasing slightly since May:

With the aim of effectively implementing monetary policy.

This is indeed what we’ve seen in tech, crypto, VC, etc. Enter SVB, etc. For more, see this previous note: