Why Does Bank Accounting Seem So Backwards?

Fixing the accounting is futile; understanding the business is what matters

The FDIC is out with its latest quarterly banking profile — on the now-infamous quarter of banking that was Q1-2023.

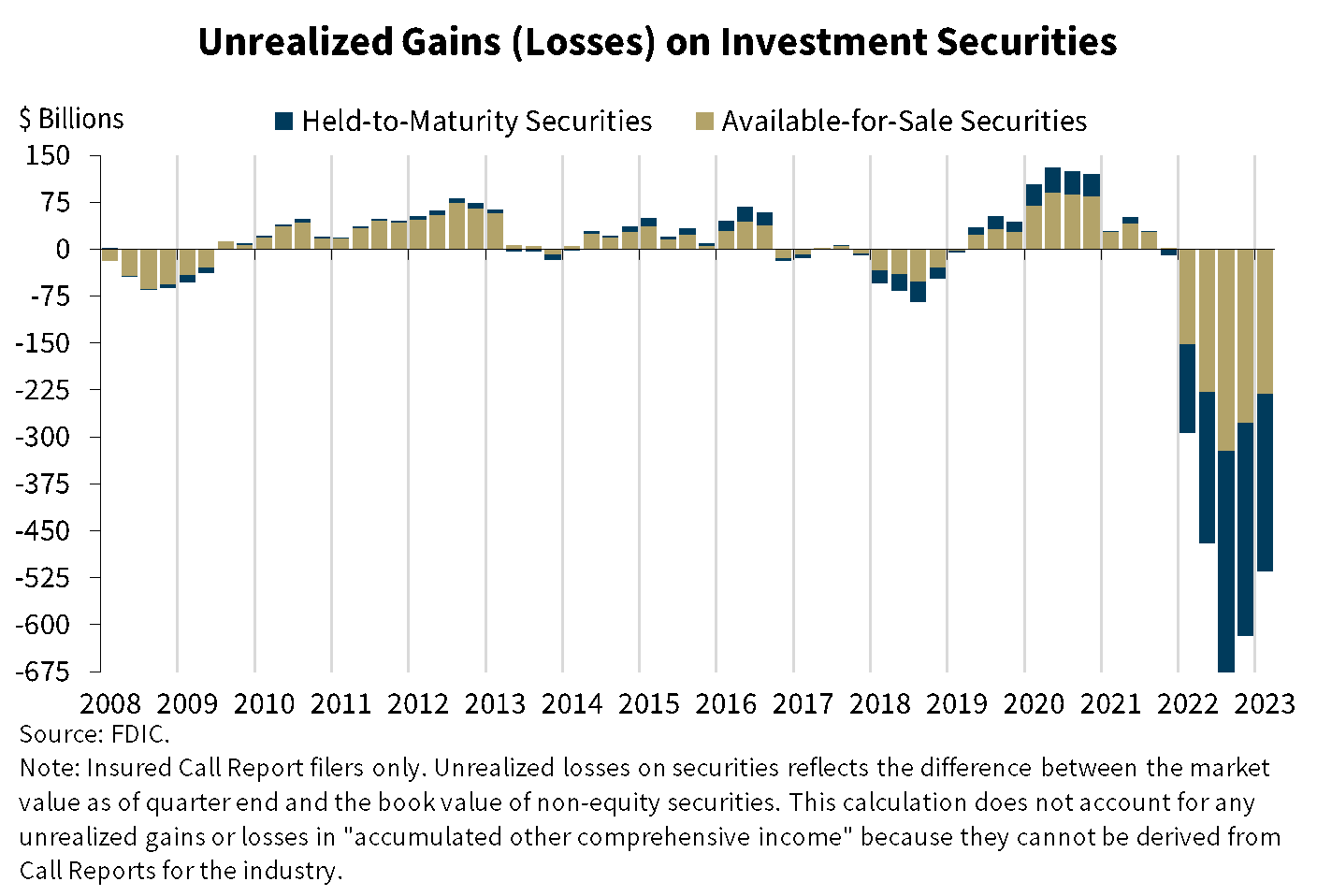

The FDIC reported banks’ unrealized losses on securities—an accounting product on which many have pinned the March bank crisis—fell by 16.5% in the quarter “primarily due to declines in medium- and long-term interest rates.” As of end-Q1, the number stood at $515 billion, down from $620 billion the previous quarter and a peak $690 billion as of Q3-2022:

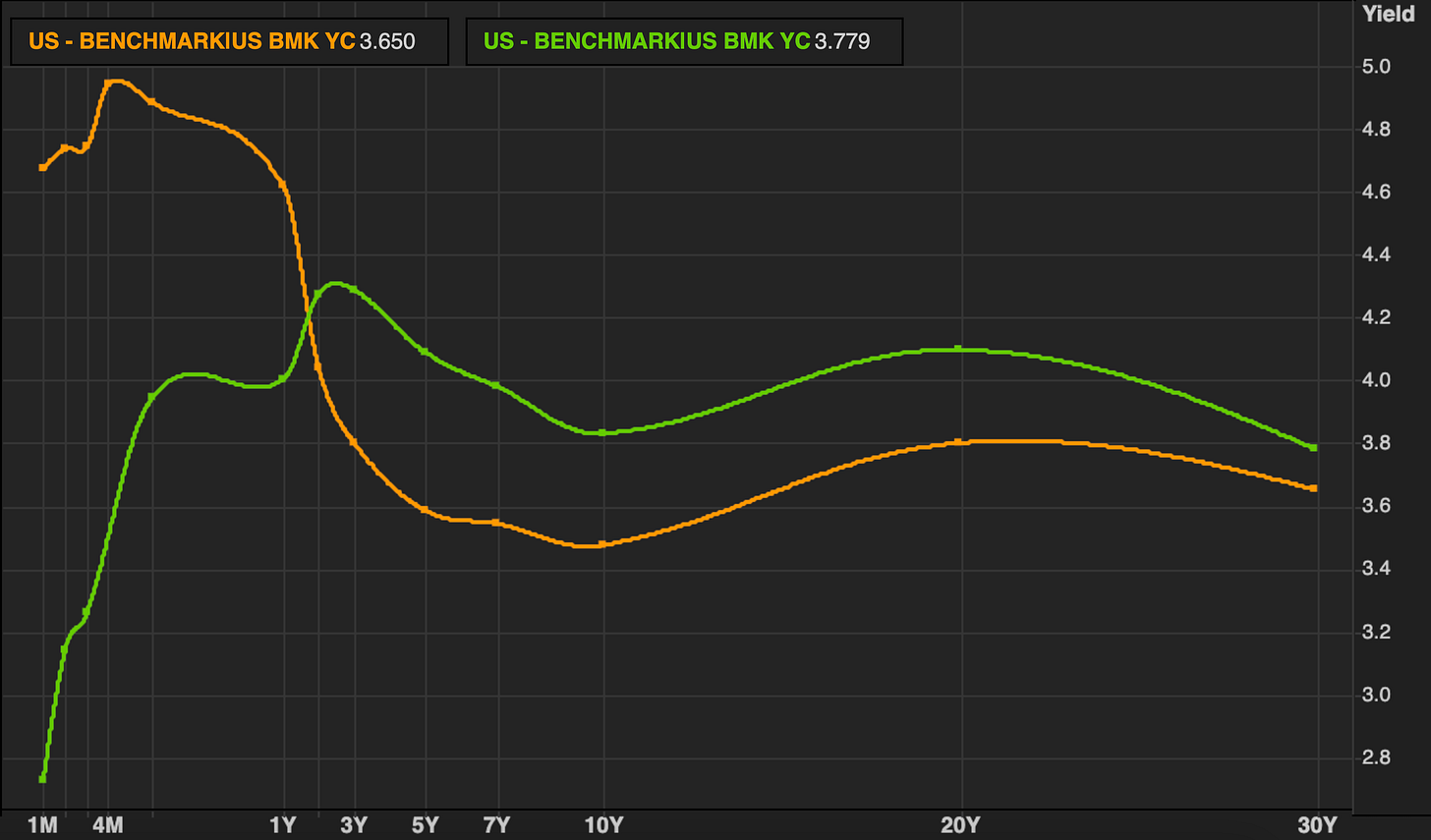

Rates

Yes, policy/deposit rates have gone up, but the above is the result of an increasingly inverted yield curve. So, short-term interest costs are expected to fall over time. Compare the 3/31/23 yield curve (orange) to 9/30/22 (green):

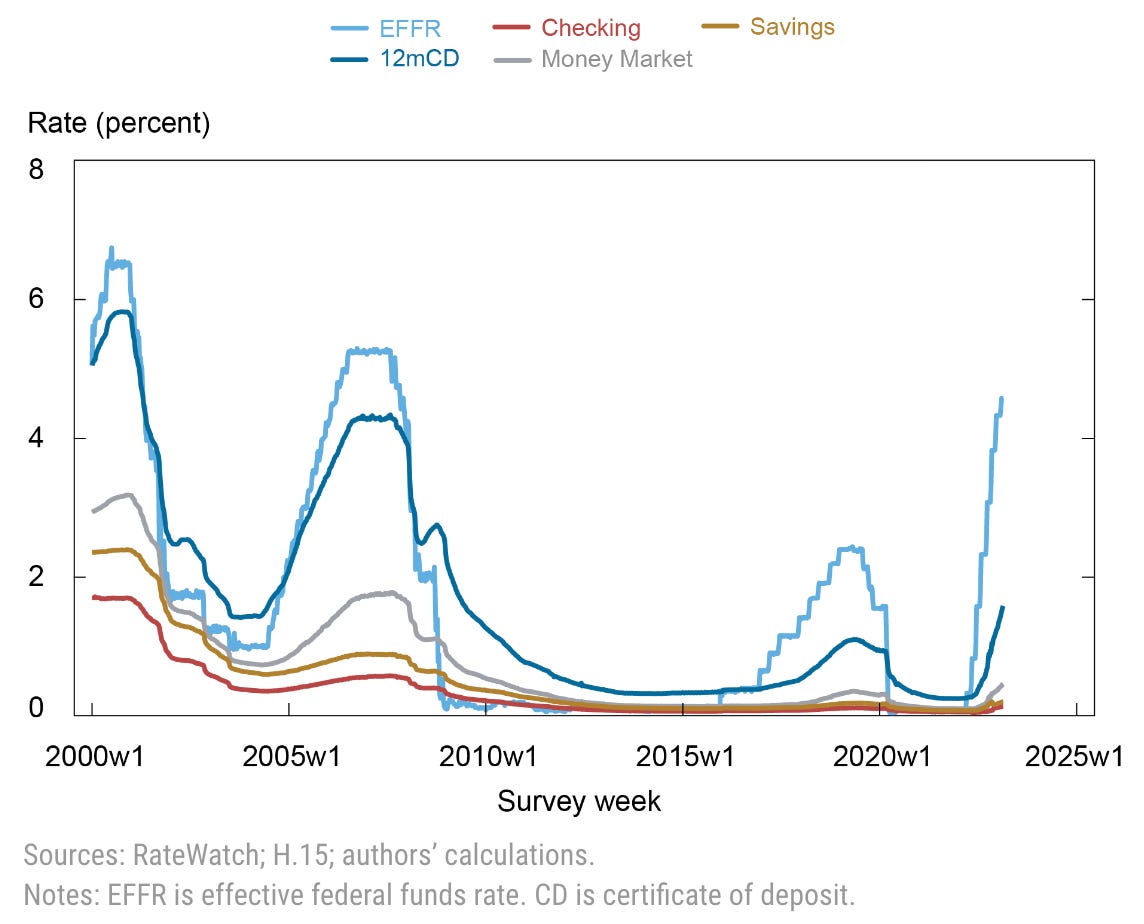

But, deposit rates notoriously don’t rise as swiftly or steeply as market rates—because deposits also pay in convenience.1 Here’s the FRBNY’s Alena Kang-Landsberg, Stephan Luck, and Matthew Plosser:

So, in some sense, marking bank assets to market interest rates is nonsensical. Banks, uniquely, don’t really pay market rates. Because their deposit debt is also their product, clients pay for it (through foregone yield).

But but: Does that mean the marks should have improved the way they did in Q1?

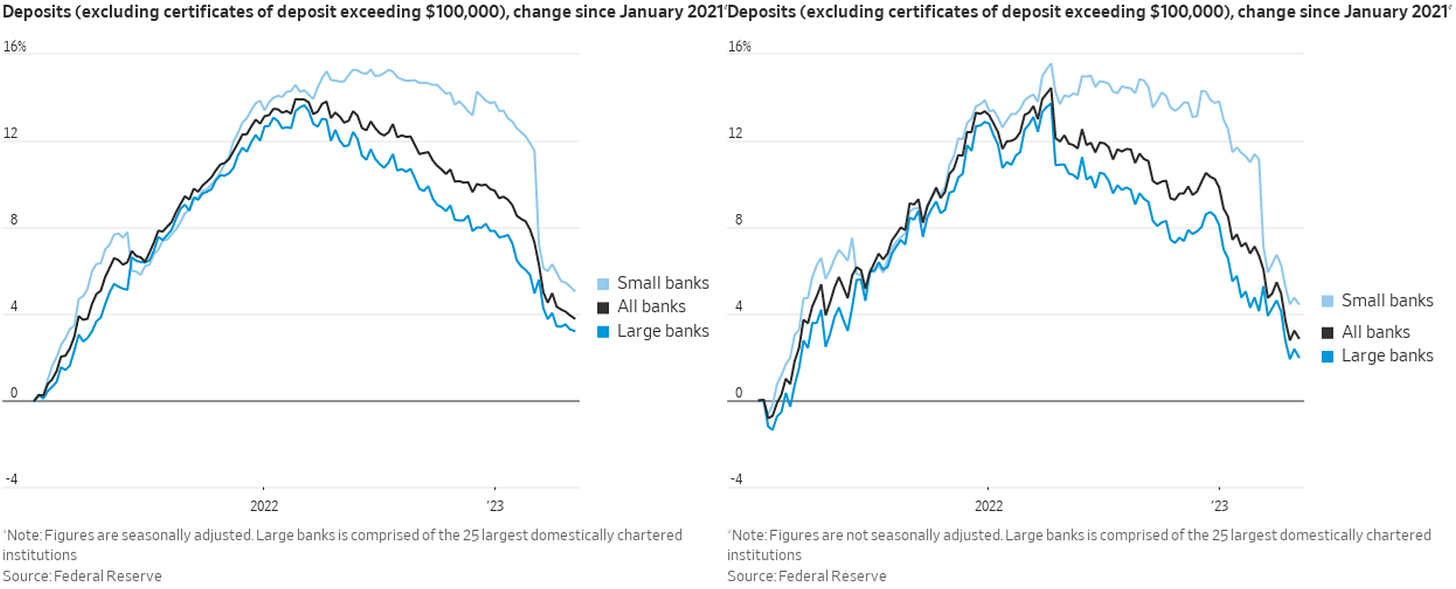

After all, Q1-2023 was a quarter marked by an increased fragility of deposits. Broadly, banks saw a sharp acceleration of deposit erosion. Here are seasonally adjusted and unadjusted figures courtesy of the WSJ’s Nick Timiraos. Note the sharp March decline:

And from the FDIC again:

This corresponded to a sharp increase in money market fund assets:

These MMF inflows either find their way back to banks via more expensive market-based routes—repo, etc.—or leave the banking system via the Fed’s reverse repo facility.

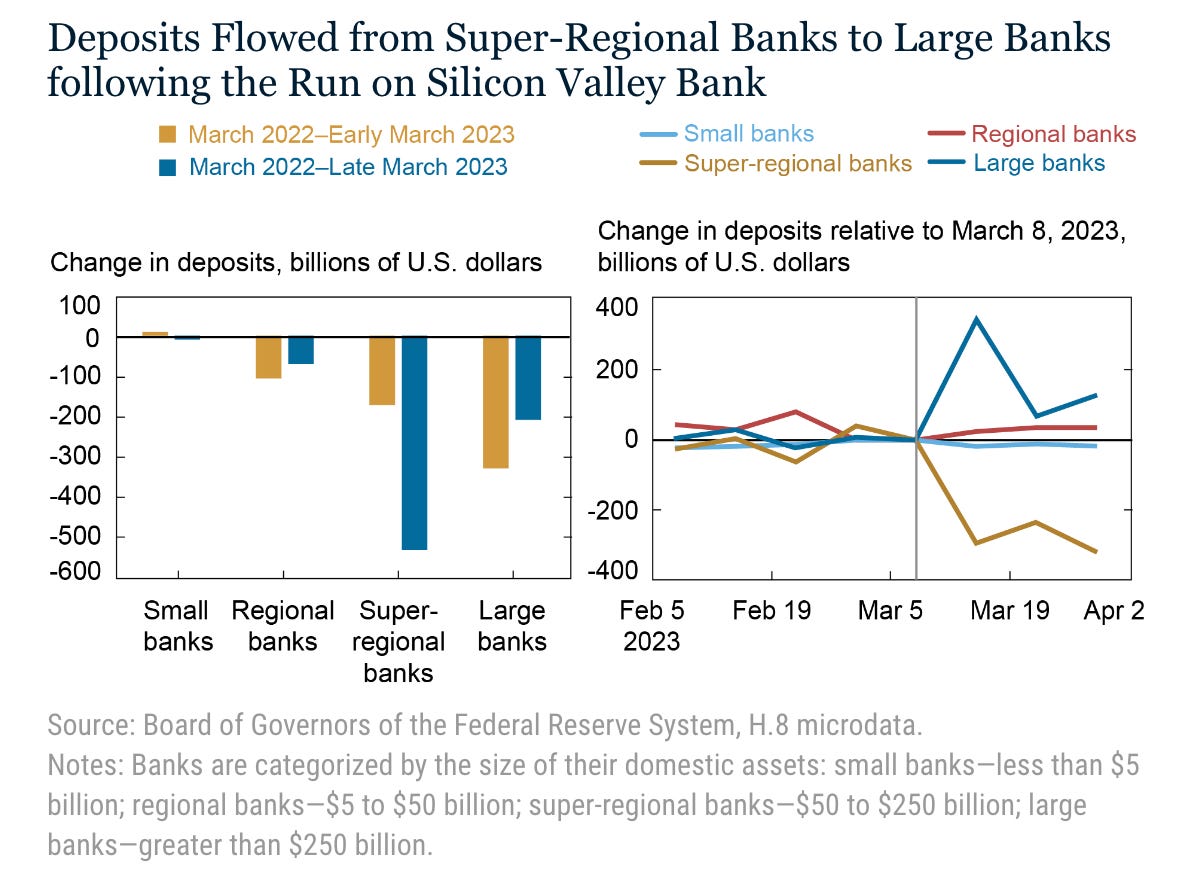

Despite this deposit precariousness in Q1, mark-to-market accounting for the quarter revalued banks’ securities higher, telling the story that banks’ funding outlook improved in Q1. The situation, however, was of course very bank-dependent. The large bank model saw deposit inflows, while banks in the next tier—where SVB, Signature, First Republic, etc. lived (and, er, died)—were not so lucky. Here’s a nice pair of charts from the FRBNY’s Stephan Luck, Matthew Plosser, and Josh Younger elucidating that:

All the above raises the question for bank accounting: marking to which market exactly?

The SVB case

Remember, no one cared who SVB was until it put on its emergency 8K filing. That was despite SVB publicly reporting its steep unrealized HTM securities losses for successive quarters. After it reported the year-end, unrealized bond losses that supposedly led to its downfall, its stock traded at $285/share.

Indeed, as with the wider industry trend noted above, SVB’s unrealized loss position on its HTM portfolio actually improved between Q3 and Q4 of 2022: The loss fell slightly in nominal and percentage terms, and it went from greater than to less than SVB’s shareholders’ equity.

Why didn’t the unrealized losses matter so much at an earlier date? Because the market didn’t understand the deposit base was in as dire straits as it was until the 8K fretted about client “cash burn.” Suddenly then, the reported mark-to-market numbers (in the notes to the financial statements, not official GAAP or regulatory numbers) start to look more accurate.

Reforming bank accounting?

So, as soon as a bank is in crisis, the mark-to-market numbers appear obviously right, and we all question why weren’t making the bank use those marks for GAAP and regulatory capital purposes this whole time.

But, those marks are still likely “wrong” for all the banks that haven’t faced a crisis. Should we assume Citigroup is going to have to realize the $30 billion of unrealized HTM securities losses it reported for end-2022? Or is it more likely that it won’t have to take those bonds to market (or the Fed), and its profits on those bonds will instead be determined by its deposit costs?

And as we’ve seen, mark-to-market numbers told a story of an industrywide funding outlook improvement leading up to and following the bank crises in March—because falling market rates were improving valuations.

So, what’s the proper “market” to mark to? The bond/repo/Fed rate curve or the much-cheaper deposit curve?

Well, it depends what kind of banking business you’re in. Accounting that would’ve made sense for SVB likely wouldn’t make sense for Citi (or JPM, BofA, etc). Accounting that made sense for SVB in 2023 would’ve made much less sense for SVB in early 2021.

If something happened that made us again start investigating bank accounting rules (check!), the rules are probably gonna look dumb. But if you change the rules so that they don’t look dumb in a crisis, they often won’t make sense outside of crisis. If it’s the GAAP rules we’re changing, then investors will ignore them sometimes—just at different times than they ignore them now—or misunderstand them altogether, leading to economic distortions. If it’s the regulatory rules we’re changing, it’ll just lead to a bunch of economic distortions as the rules won’t reflect reality.

As we’ve seen, the correctness of the asset valuations depends on the bank’s business model. That can’t be assessed on the market’s behalf by accounting rules.

Bank accounting is hard. “Fixing” it won’t solve the 2023 kind of bank run.

Comments welcome via email (steven.kelly@yale.edu) and Twitter (@StevenKelly49). View Without Warning in browser here.

And, sometimes, insurance—and other government support benefits.