The BTFP and Fed Lending When Rates are Volatile

It’s a big balance sheet world out there

The Fed said on Wednesday night that the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) would sunset as planned on March 11. The Section 13(3) emergency lending facility, introduced in the immediate aftermath of SVB last March, lends to banks against the par value of monetary-policy-eligible securities (effectively, Treasury and agency securities) for up to a year (no prepayment penalty) at a rate of 1-year OIS + 10 bps. Also in the Wednesday night announcement, the Fed would henceforth set a rate floor on the BTFP at the interest on reserves (IOR) rate—the rate the Fed pays banks on their reserve balances.

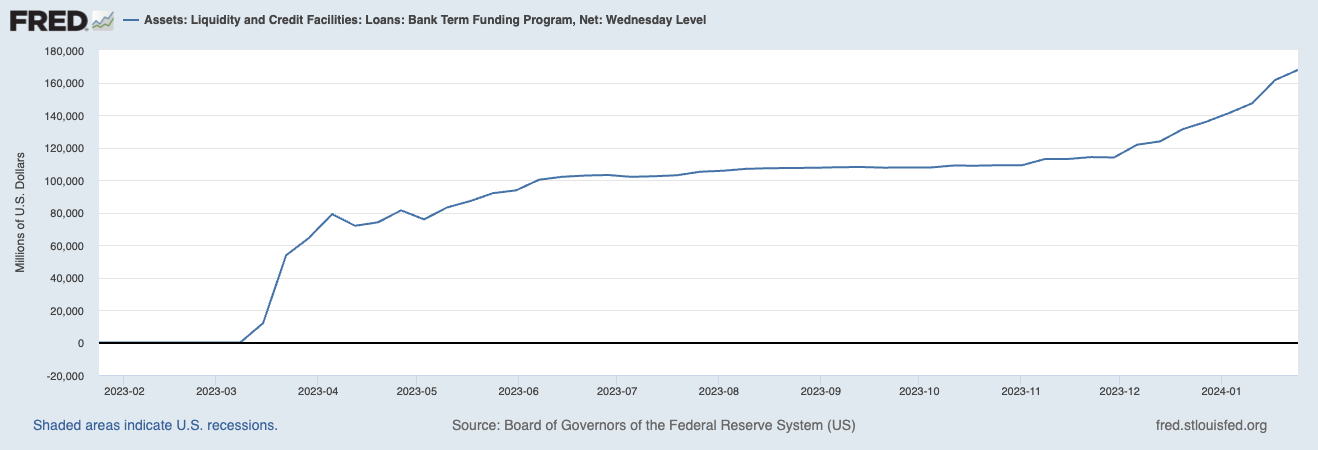

Prior to the adjustment, the BTFP hit a new peak of approximately $168 billion, despite the continued absence of the bank run conditions under which it was introduced:

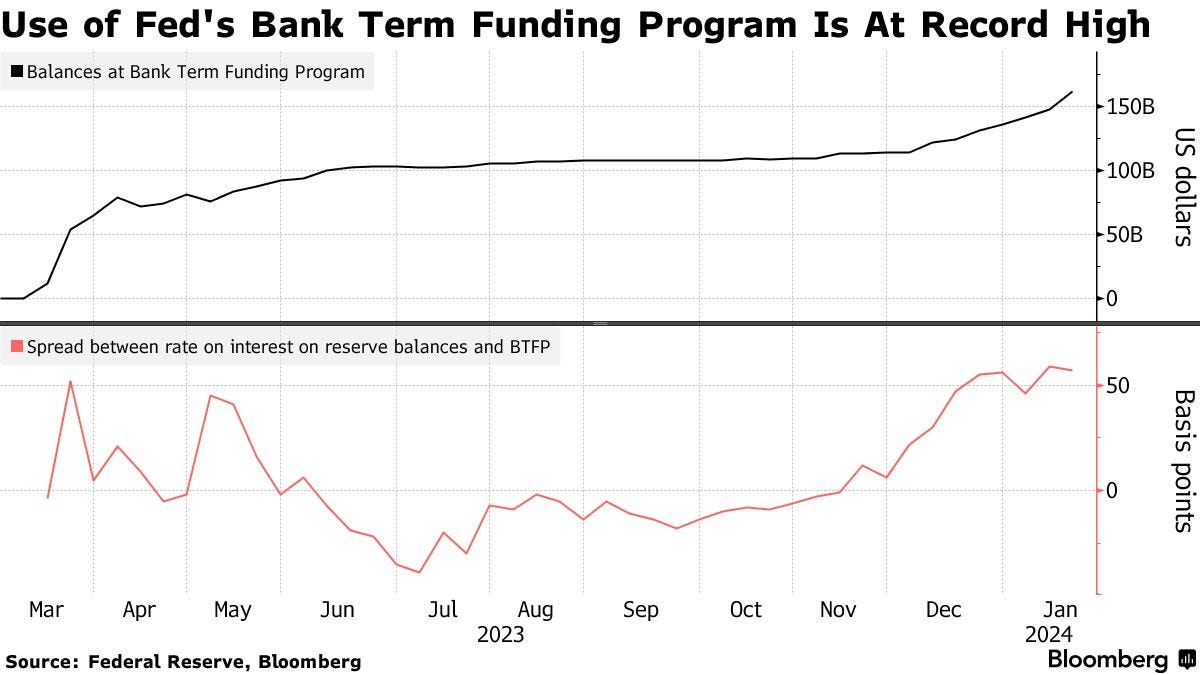

The 10 bps above 1-year OIS was in theory a penalty over market pricing, and OIS was/is already hundreds of bps more expensive than the deposits that banks were replacing with the BTFP. Yet, because of the ongoing yield curve inversion, which has recently also become persistent at the front end of the curve (i.e., at 1-yr OIS) due to many expectations of incipient rate cuts, a theoretical arbitrage has been structurally available:

With the Fed targeting a range of 5.25%-5.50% for the fed funds rate, it has been paying 5.40% on banks’ balances of reserves since July. With the OIS+10bps hanging out under 5%, a nice arbitrage opens up where a bank borrows from the BTFP and does nothing with the newly minted money from the Fed but collect the IOR. A 50-bps carry is not nothing.

Worse yet, given the persistence of this negative carry for the Fed of late, this infinitely profitable trade was being infinitely advertised in the press: the WSJ, Bloomberg, the Economist: “How America accidentally made a free-money machine for banks”, etc.

Naturally, the Fed was quickly responsive to the press spotlight on this and closed the loophole on Wednesday night (in addition to confirming that the facility wouldn’t be extended in March). The Fed “losses” to this theoretical arbitrage are likely small but point to a bigger challenge for the Fed too.

But First: Tempering the Cynicism

Firstly, it’s worth noting the few reasons why this “free money” in the way it’s been characterized—where banks borrow from the BTFP solely to capture the carry at the Fed—was still mostly theoretical.

Bank leverage ratios: So much of the post financial crisis, post Dodd-Frank story in markets has been about how limited banks now are when it comes to picking up small arbitrage opportunities due to capital requirements. The cost of equity weighs on any arbitrage available here.

Stigma: The Fed is legally required release the names of all the borrowers in Section 13(3) programs no later than one year after the program closes. There is stigma to borrowing from emergency programs.

This stigma—which is normally a bad thing for the central bank—can be ameliorated by favorable terms; i.e., you want the bank to be able to say “we were never worried, it was just a good deal relative to the market.” However, this lack of stigma can go in reverse if that quote drifts into “we flat-out took advantage of the taxpayer for free money.” So each end of the spectrum in this case risks reflecting poorly on the bank, for limited gain.

Supervisors!: No one was more aware of the calm banking conditions and the potential BTFP arbitrage than the Fed. So, if a bank was showing up in January 2024 saying “yeah we want to borrow $50 billion from the BTFP,” the Fed was at least going to be like “you sure you wanna do that?” and hope the bank scurried away.1

Also, that the BTFP has been setting a “new record” every week lately sounds less extreme when compared to the world of eligible collateral. Banks are sitting on over $4 trillion of Treasury and agency securities—and that is at accounting value, so the trading and available-for-sale portfolios (and some HTM) would need to be marked up to par to find the full borrowing capacity of those securities. (Plus, Treasuries and agencies aren’t technically the only eligible securities.) BTFP volume of $168 billion isn’t outrageous in front of that backdrop.

Possible explanations for the recent bump in volumes:

The arbitrage could certainly be playing a serious role of late.

Especially with banks who can get away with it. Some community bank not supervised by the Fed that has no headline risk… sure why not.

Too, the BTFP uses the discount window infrastructure. Supervisors have been encouraging banks to preposition more collateral at the discount window in the aftermath of March 2023—which they have been doing. As the amount of collateral sitting at the discount window has increased, it’s less of a process for the bank to post it to the BTFP. So, as long as the BTFP is open and the spread is positive…

The impending BTFP expiration & fragile banking conditions.

Lest we forget: Banks are still sitting on high unrealized losses; some banks in particular are worried about deposit flight or further spikes in deposit betas; commercial real estate is a growing issue on the market’s mind.

The BTFP locks in a year of funding as a nice hedge against all the above for banks who might not have access to the private equivalent (or at least not at as good a price).

But no doubt, this latter, more-benign motive is furthered by the increasingly favorable pricing of late—irrespective of the IOR arb. Moreover, it’s not clear the Fed should be in the business of providing this kind of economic insurance outside of true crises (nor does it want to be, clearly!).

The awkwardness of ELA in a non-ZIRP world

Adjacent to all this is the story of the big Fed balance sheet and how its steady gains from buying long and paying out short rates (or nothing at all in the case of currency) have slipped into billions of dollars of losses following its steep rate-hiking campaign. The BTFP losses may further underline the cause of those who want the Fed to return to its pre-GFC mode of operation, where its balance sheet was smaller and rates were implemented via reserve scarcity, rather than paying interest on reserves.

The BTFP and its recent arbitrage-ibility have very visibly added another layer to that story: The cost—in a literal sense—of emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) is higher when interest gets paid on those reserves. Wednesday’s announcement showed the Fed was correcting for the negative carry it was getting on new BTFP loans, but the pricing change only brought the net carry to zero.2

In itself, this is totally fine. The goal of ELA is not (or should not be) to make money. But the Fed is legally obligated to not ex ante expect to lose money when implementing ELA. This is part of why the Fed has historically taken first-loss funding support from the Treasury for some riskier programs—the more loss protection, the more generous a program the Fed can set up ex ante. But, these program designs have not historically considered the interest costs to the Fed. They were typically effectively zero in the GFC and during COVID—because the Fed cut rates to zero in both crises and sought to keep them low and stable for a long time.

The Fed’s most recent report to Congress on the BTFP shows revenue of about $4.1 billion as of 12/31/2023. Not mentioned as part of the program is the approximately equal (nay, slightly higher) interest expense on the reserves associated with the BTFP. The Treasury committed $25 billion of ESF funds “as credit protection to the Federal Reserve Banks in connection with the Program.” That coverage seems clearly not inclusive of interest-on-reserves-induced losses the Fed bears.

Rates Were Never Gonna Go Up

A perhaps less charitable, if also less in-the-news, example is the Fed’s PPPLF program from COVID. The Paycheck Protection Program Liquidity Facility provided liquidity for banks participating in the SBA’s PPP assistance, which provided government-guaranteed loans to businesses during the pandemic.

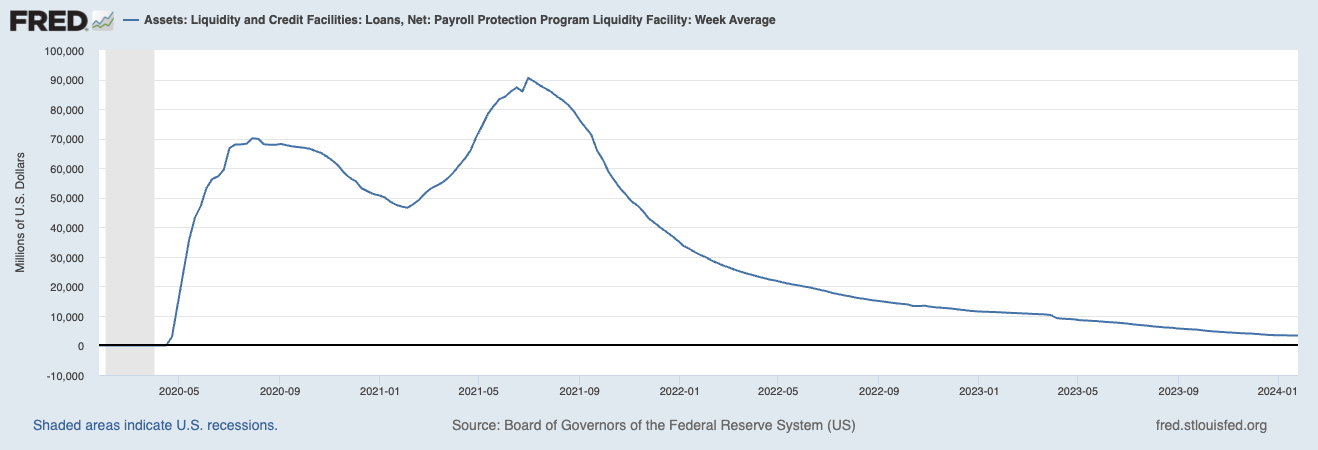

The Fed’s PPPLF loans essentially took the PPP loans off the banks’ books; the PPPLF lent the principal amount of any posted PPP loans for the entire duration of the loans. PPP loans were for either 2 or 5 years, so PPPLF loans have persisted on the Fed’s balance sheet—still at over $3 billion, after peaking above $90 billion in 2021:

The Fed charged a fixed interest rate of 0.35 percent on PPPLF loans—a rate which was then 10 bps over the primary credit rate, and 25 bps over the IOR rate. Given the airtight collateral (government guaranteed) and valuations, the Fed took no credit protection from the Treasury. The Fed’s latest submission to Congress on the PPPLF reports that, “the amount of interest, fees, and other revenue or items of value received under the facility, reported on an accrual basis, was $456,792,726.”

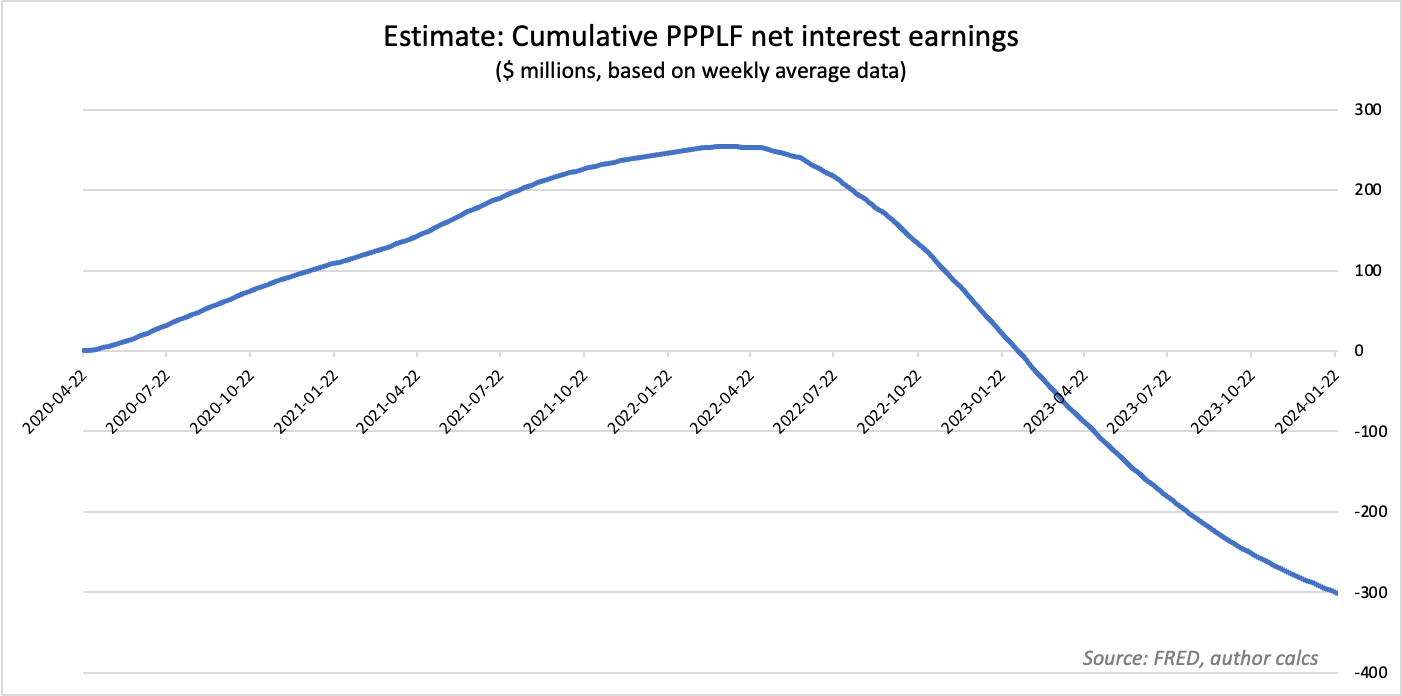

A back-of-the-envelope calculation of average weekly balances at the PPPLF earning 35 bps similarly suggests $457 million of interest earnings through this week. However, running the same calculation for IOR also reveals associated interest costs of $759 million, tipping net interest earnings negative:

The Fed is likely not really considering this a loss of $300 million on a 13(3) facility (which will indeed have zero credit losses), and this is much more of a drag on Fed earnings than the much-maligned-recently BTFP.

If the Fed did include these interest costs in assessing emergency liquidity programs (and the discount window), meeting its legal minimum for being satisfactorily secured—that it ex ante expect no losses—would be that much more difficult. In practice, that would mean either tighter lending terms or requiring more protection from Treasury (or other external) funds. (For instance, the Fed shifting to all floating-rate loans with an IOR floor would imply greater credit risk.)

That’s not to suggest that having an IOR system should move the needle on the legal standard for emergency liquidity. But, as with other balance sheet assets, emergency lending is less lucrative—and may be loss-inducing even absent credit losses—for the Fed in an interest-on-reserves world. The Fed will always technically be playing with yield curve fire, just as it does with QE.

While (the royal) we want to get rid of this kind of supervisory shaming at the standing discount window, it’s almost certainly appropriate for a 13(3) program when crisis conditions have receded and banks might be trying to game it.

This doesn’t change the pricing of existing loans, however. The negative carry the Fed has on many of the outstanding BTFP loans is unaffected.