Is the Fed Financing the FDIC?

Maybe casually

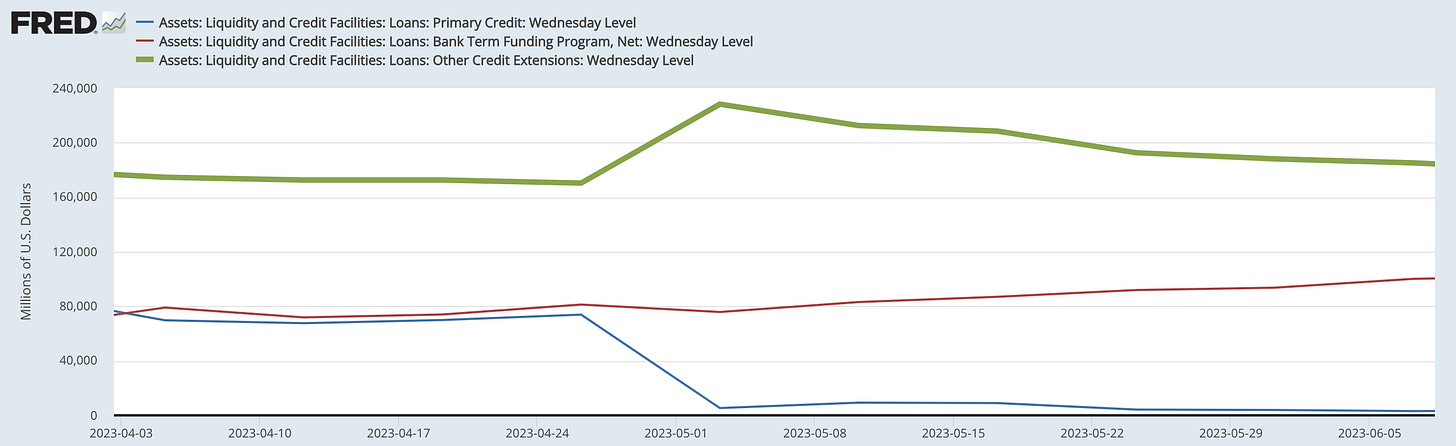

Here’s the Fed’s discount window lending (blue), Bank Term Funding Program lending (red), and so-called “other credit extensions” (green):

“Other credit extensions” is the collection of Fed funding to institutions that had failed and are being resolved by the FDIC—SVB, Signature, and First Republic.

The Fed had lent via the discount window to SVB and Signature prior to failure1 and to the FDIC bridge banks created for each prior to their sale. The Fed lent to First Republic via the discount window and the BTFP prior to its failure and immediate sale to JPMorgan (there was no bridge bank).

And, as the Fed wrote in June [emphasis added], the Fed loans were left behind by the failed banks’ acquirers:

Upon the two bridge depository institutions and First Republic Bank being placed into receivership, the discount window and BTFP loans were not assumed by the acquiring depository institutions. In each case, the outstanding discount window and BTFP loans are being repaid from the proceeds of the sales to the acquiring depository institutions, if any, and the recovery on the collateral that was left behind in the receivership, supported by the FDIC guarantees of repayment.

As shown above, of the bank lending programs, the “other credit extensions” lending to FDIC-run institutions quickly became the largest (almost $240 billion)—and has stayed in the lead.

Is This Normal?

Where does the FDIC get its money?

While FDIC obligations have the “full faith and credit” status of US Treasuries, the FDIC is not funded by congressional appropriation; it is funded primarily by the fees it assesses on the banking industry. The Deposit Insurance Fund ended 2022 at $128.2 billion and Q1-2023 at $116.1 billion. The FDIC has $200 billion of credit lines with the Treasury: technically, $100 billion with Treasury and $100 billion with the Treasury’s Federal Financing Bank.2 It can also borrow from the FHLBs and from banks themselves. It has no specific statutory authority to borrow from the Fed.

Total FDIC borrowing is subject to a formulaic cap:

The FDIC borrowed during its cleanup of the savings & loan crisis of the 1980s and 1990s. Yet, when the DIF balance went negative during the Global Financial Crisis, the FDIC didn’t do any borrowing kinda sorta because of Fed financing…

FDIC funding during the GFC

As shown in this FDIC chart below, the DIF balance went negative in 2009. The “balance,” however, adjusts for expected losses; it is not an accounting of the FDIC’s liquidity. The DIF stayed liquid without any FDIC borrowing.

As shown, the FDIC effected a small special assessment of $5.5 billion in June 2009. However, it later raised its liquidity via an elegant mechanism: a prepayment from banks of their regular insurance premiums to the FDIC. In December 2009, it raised over $45 billion by requiring banks to pay their normal quarterly payment, plus the next 12 quarters’ worth—so the DIF could stay highly liquid despite a temporarily negative balance.

In addition to a desire to avoid drawing on its credit lines for a variety of political, operational, and terms reasons during the GFC, the FDIC also wanted to avoid imposing another special assessment—as that would be booked as a large expense for the already-fragile banking system. As the FDIC later said, “In the second quarter of 2009, when the special assessment was charged, FDIC-insured commercial banks and savings institutions reported an aggregate net loss of $3.7 billion.”

A prepayment of their regular assessments, however, had the benefit that banks could book it as an asset, and book the expense slowly over time.

Where the Fed comes in…

Ok, but no free lunch, right? Wasn’t this still pulling $45 billion of the system’s liquidity at a fragile time? Well, at this more chronic and less acute stage of the crisis, liquidity was less the issue. The Fed had injected then-record amounts of liquidity via QE (and emergency operations), and the FDIC assessed that banks were essentially sitting on excess liquidity.3

In this sense, the FDIC’s liquidity was sort of supplemented by the Fed. Of course, it does not seem there was any intent (or discouragement) by the Fed for such.

2023 flash-forward: The FDIC funding issues of the GFC occurred well into a recession, when the Fed was executing QE and worried about deflation. The 2023 concerns over a FDIC funding are occurring in the exact opposite situation.

With money markets worried the Fed’s QT is going to overshoot the so-called “lowest comfortable level of reserves,” it’s not clear how comfortable the FDIC (and Fed) would be with an industry prepayment in the current moment.

“Other Credit Extensions” is Pretty Abnormal

At least back through 2003, “other credit extensions” has never shown up in the Fed’s weekly balance sheet report of its Wednesday balances. However, it shows up in the “week average” figures—thanks to Bear Stearns:

As a bridge to the weekend—when JPMorgan ultimately bought most of Bear—the Fed did an emergency loan to Bear on Thursday night/Friday morning. The loan was ultimately for $12.9 billion and was paid off in full Monday morning—hence its nonexistence on the bookending Wednesdays. The Fed invoked its Section 13(3) emergency liquidity authority but structured the loan as a back-to-back loan via the discount window: the Fed lent to JPM (without recourse), which on-lent to Bear and took Bear’s collateral to the window.

Ergo, “other credit extensions.” Yet, no FDIC involvement in this case of the odd Fed balance sheet item.

Is the Fed Financing the FDIC in 2023?

Answering this question can’t be done via a straightforward accounting of inflows and outflows with respect to resolutions given the disparate/incompatible public disclosures from regulators and banks—and due to the rapidly changing nature of bank balance sheets in their end-days. However, there is evidence in the public data.

First: why?

What would be the FDIC’s incentive to not pay back the Fed immediately upon asset sales in resolution? A few reasons come to mind:

Lots of uncertainty over when a line can truly be drawn under the banking stress—and thus how much liquidity the FDIC will ultimately need—especially given the failed institutions’ size (see below). FDIC concern over this risk is likely fading by the day (and, indeed, we see a gradual reduction of “other credit extensions”).

Source: FDIC The debt ceiling. With late-spring’s imminent approach of the debt ceiling, you could see why the FDIC would be nervous about its ability to call on Treasury or issue its own debt to banks—which would count against the public debt limit.4 As of the June debt ceiling suspension, this risk is off the table until 2025.

If it were cheaper? (It’s not. More below.)

(The FDIC only got $10.6 billion of cash in the First Republic sale, and it got no cash inflow in the SVB and Signature sales.)

Notable before moving on: It also kind of doesn’t matter that it’s the Fed holding these debts. These loans could just as well have been made by, say, Apollo, and the FDIC could be maintaining outstanding balances all the same. (We just wouldn’t have the weekly balance sheet data like we do from the Fed.)

What Do We Know?

The Fed and 13(3)

The Fed established the Bank Term Funding Program—under Section 13(3)—rapidly in March to provide liquidity to banks against the par value of some of their assets. The Fed staff memo to the Fed Board proposing the facility is not public. However, a GAO report describes the memo’s contents. To invoke Section 13(3), the Fed Board must have a finding of “unusual and exigent circumstances.”

Notably, the Fed memo lists the potential stress on the FDIC’s liquidity as one of those circumstances according to the GAO:

In FDIC Receivership

As noted above, in none of the purchases of the failed banks did the acquirers assume the Fed debts. As noted in the initial excerpt from the Fed, this debt has become backed by an FDIC guarantee of repayment—that is, “the full faith and credit of the United States.” The Fed noted the discount window loans to SVB and Signature bridge banks were subject to an FDIC guarantee, as were the First Republic discount window and BTFP loans.

You’d think the FDIC guarantee would make the Fed extremely comfortable. Normally, the discount window and BTFP charge a slight premium to the policy/Treasury rate. Yet, per the Fed [emphasis added]:

The outstanding loans accrue interest at 100 basis points above the applicable discount window or BTFP rate until they are repaid in full. The Federal Reserve expects that these loans will be repaid in full before the end of 2023.

So, the FDIC is paying the Fed a 100-basis-point premium relative to what private banks pay—including First Republic in its last days and the bridge banks.

It’s also worth mentioning that the FDIC provided $35 billion of seller financing into First Citizens’s purchase of SVB and $50 billion into JPM’s purchase of First Republic. The loan to First Citizens charges 3.5% and the JPM loan charges 3.4%.

First Republic Tells Us a Lot

JPM took effectively all of First Republic’s assets. In the SVB and Signature cases, the buyer of each franchise only took part of the balance sheet—and only loans from the financial asset pool. And, we don’t know which assets of SVB and Signature bank were posted at the Fed discount window—which takes both loans and securities.

First Republic was able to borrow from the BTFP (the other two banks failed before it was established) and the window, plus JPM took effectively all of its assets immediately upon failure, so we can glean a few things.

In its last pre-failure earnings release, First Republic shared having about $14 billion of BTFP borrowing and $64 billion from the discount window:

In its order taking possession of the bank, the California state regulator said First Republic had a total $93.2 billion borrowed from the Federal Reserve as of close of business on April 28 (the Friday before its failure).

In the Wednesday snapshots of the Fed’s balance sheet that bookend the date of First Republic’s failure (May 1), “other credit extensions” increased by $58 billion, suggesting First Republic’s total Fed borrowing was at least still that latter number:

In addition to “other credit extensions” not falling back to its pre-First Republic balance for a couple months, it’s clear First Republic’s BTFP loan is still outstanding. On top of the Fed’s Wednesday balance sheet reports, it also reports month-end balances of the BTFP to Congress. In these reports, the BTFP totals have—since May—consistently run approximately $14 billion above what the Fed reports in its weekly balances charted above. (On May 31, it was both a month-end and a Wednesday. The Fed’s weekly balance sheet reported $93 billion; its report to Congress said $107 billion.) This difference is the outstanding First Republic BTFP loan.

What does this all mean? Well, certainly in the case of First Republic, all or effectively all the collateral that was posted to the Fed was sold to JPMorgan. So there’s no collateral left at the Fed—which means the FDIC either replaced the collateral with its Treasury holdings (unlikely given the likely size of uncollateralized Fed lending, that this would like a direct loan from the Fed, and that it would expensively add little relative to selling the Treasuries) or, more likely, simply replaced the collateral altogether with the FDIC guarantee.5

Procedural detour: The FDIC it invoked the “systemic risk exception” to its normal statutory requirement for “least-cost” resolutions for SVB and Signature, but only explicitly to guarantee uninsured deposits. And the FDIC did not invoke the exception for First Republic. But it can probably argue that this setup still ends up being “least-cost.” However, the 100-basis-point premium being charged by the Fed certainly at least makes that calculus tougher…

The Fed is likely just playing ball here and letting the FDIC sell the collateral out from under the Fed loans. But, at least in the case of First Republic’s BTFP loan, we know the FDIC isn’t paying down the Fed following the sale of the underlying collateral. Thus, if nothing else, we can say with virtual certainty that the Fed’s BTFP loan to First Republic is now “financing the FDIC.” Presumably there are other loan balances like this from the three banks’ discount window borrowings.

But should/do these loans count against the FDIC statutory borrowing limit? And the debt ceiling? (The FDIC explicitly said in the Federal Register in 2009 that the prepaid assessment of the industry was “not a borrowing.” That, however, cost the FDIC no interest.) Should they be classified as borrowing from the Fed, something not provided for in the FDIC’s borrowing statute?

To be clear: Aside from the legal questions, there doesn’t seem to be anything inherently sinister about this setup. It may be notable as a financing tool for the FDIC to use (or repurpose in a more legally conforming way) in the future: To the extent it can sell collateral out from under any failed banks’ loans that it assumes and replace that collateral with an FDIC guarantee, it can create liquidity for itself.

9/17/2023 UPDATE – new evidence: https://www.withoutwarningresearch.com/p/update-new-evidence-on-is-the-fed

9/24/2023 UPDATE – FDIC partial paydown: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/fdic-borrows-50-billion-pays-down-some-debt-fed-steven-kelly

Comments welcome via email (steven.kelly@yale.edu) and Twitter (@StevenKelly49). View Without Warning in browser here.

Oddly, the Fed seems to suggest that only Signature’s bridge bank took on discount window loans from its predecessor. It does not the say the same of SVB, to which the Fed only says it lent before and after the bank’s failure. Here’s the Fed [emphasis added]:

Discount window loans were extended to Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic Bank, and BTFP loans were extended to First Republic Bank, in each case, before the depository institutions were placed into receivership. The Signature Bank discount window loans that were outstanding when the depository institution was placed into receivership were assumed by Signature Bridge Bank, N.A., an OCC-chartered insured depository institution. In addition, new 10B discount window loans were extended to Signature Bridge Bank, N.A. and Silicon Valley Bridge Bank, N.A., both OCC-chartered insured depository institutions that were eligible discount window borrowers under the Federal Reserve Act.

SVB’s bridge transfer agreement that established the SVB bridge bank, however, says that the SVB bridge bank took on all secured obligations.

This all would seem to suggest that SVB had no outstanding discount window loans at the actual time of its failure? Hmm. Perhaps because it failed in middle of the day? I’m not sure.

There was also a built-in exemption process—FDIC discretion or a individual bank application—for any bank that would have been materially adversely affected by the liquidity grab.

Oddly, while the FDIC’s borrowing statute makes it clear that FDIC debt issued to banks applies toward the debt ceiling, it does not say so for issuing debt to the FHLBs…

An FDIC guarantee, as an obligation of a US agency (in this case, one with full faith and credit—i.e., better than the GSEs even), would even make the “collateral” still BTFP-eligible. The BTFP accepts all collateral eligible for the Fed’s open market operations, which includes the debt of government agencies. However, the BTFP requirement that the borrowing institution have held the collateral as of March 12 is less clearly satisfied. But also, like, whatever.