An Operation Twist for Treasury Market Stability

The Fed can do better than the Bank of England

While the U.S. financial policymaker complex is focused on structural reforms for improving the functioning of the Treasury market, none will be in place in the short-term (year-end cometh!). With the Treasury market functioning but strained, concern is rising that the Fed may face a situation like the recent, heavily covered government bond (gilt) market blowup in the U.K.

The Bank of England responded to the leverage squeeze in the long-term gilt market by delaying its quantitative tightening (QT) plan to begin selling £80 billion of gilts over the next year. It also got authorization for £100 billion of gilt purchases, but announced just a £65 billion purchase program—and purchased less than £20 billion.

While the gilt market blowup was due to the uniquely material use of “liability-driven investment” (LDI) strategies among U.K. pension funds, a similar market breakage could occur in the U.S.—given low Treasury liquidity, hawkish monetary policy, and high rate volatility, among many other fragilities—without the same specifics.

Indeed, the latest Fed minutes, released this week from their meeting in early November, revealed the following:

A few participants noted the importance of being prepared to address disruptions in U.S. core market functioning in ways that would not affect the stance of monetary policy, especially during episodes of monetary policy tightening. Several participants noted the risks posed by nonbank financial institutions amid the rapid global tightening of monetary policy and the potential for hidden leverage in these institutions to amplify shocks.

As the Fed plans for (and maybe starts communicating in advance of?) such a situation, it should think about mixing open mouth operations with the outlines of an open market operations strategy it hasn’t used since the post-GFC slump: Operation Twist.

Operation Twist

Colloquially dubbed “Operation Twist” (after a similar program instituted in the 1960s for different reasons), the Fed’s “Maturity Extension Program” in 2011-2012 bought $667 billion of long-term Treasuries and sold an equivalent amount of short-term ones. The aim was to balance the desire to provide additional stimulus while nodding to concerns about the size of the balance sheet. Operation Twist sought to put downward pressure on long-term rates—and thus provide additional accommodation—and was expected to have an asymmetrically small impact on short-rates given the Fed’s strong forward guidance about the Fed funds rate.

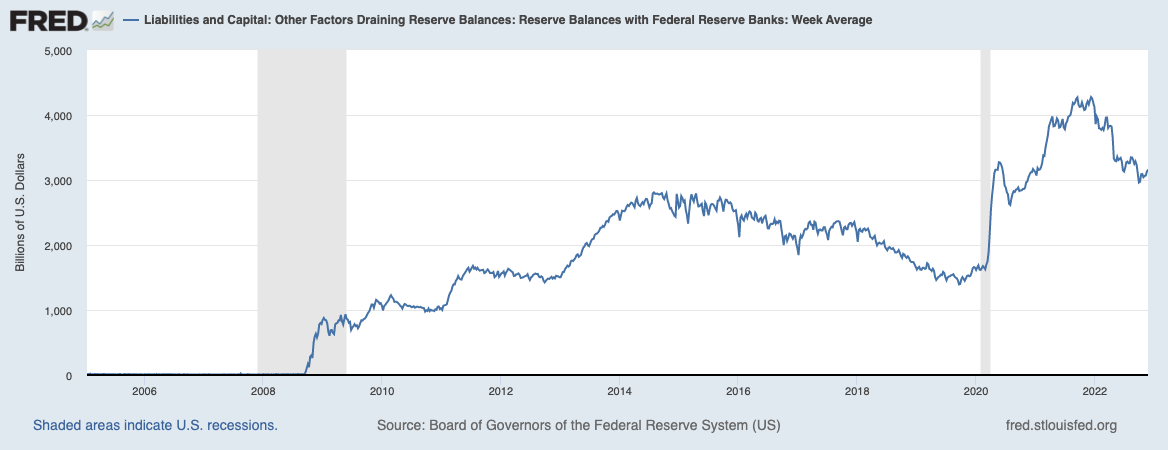

Quick detour: This may have actually been useful tool for the Fed to revisit in 2021 given their desire to provide additional accommodation and that money was piling up in the overnight reverse repo facility.

An actual Operation Twist would have released short-term collateral to a market starving for it—and would’ve likely made the Fed’s later, abrupt pivot to hawkish policy somewhat easier and less disruptive. Not to mention, less reserves in the system would’ve also meant less hindering of bank balance sheets by increasing their Supplementary Leverage Ratios.

To be sure, there are stability benefits from more reserves being in more places at once, but these benefits likely went asymptotic at some point in 2021 (or late 2020), and the Fed could’ve changed gears to an Operation Twist comfortably.

Anyways, back to 2022…

The BoE Almost Got Away with It

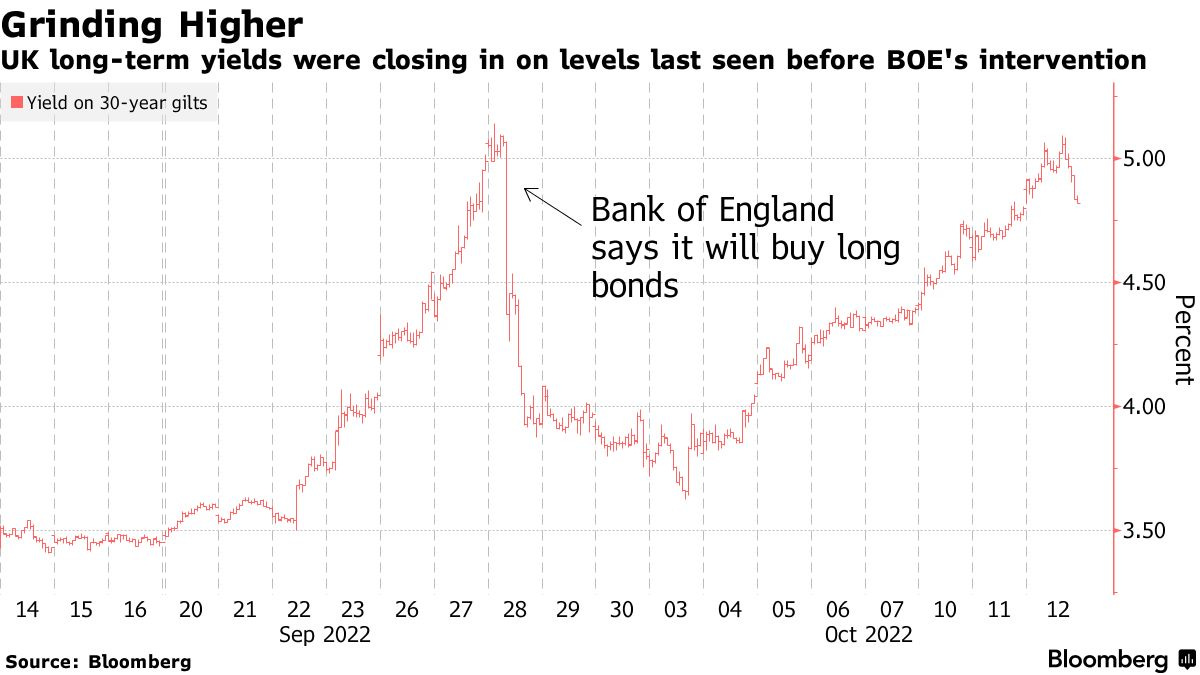

Rather than simply arresting monetary tightening, the BoE’s purchase commitment limited any market stability fallout while allowing market interest rates to continue to grind higher in a more orderly fashion:

However, and while it was brief, the BoE’s delay of QT likely was unnecessary. And it only sowed confusion in the market about the Bank’s resolve to continue tightening in the face of market breakage.

This was despite the BoE doing everything largely “right” from a design perspective (reverse auction not outright buying at any price), communication perspective (paraphrasing: “temporary and only for financial stability reasons!”), and procedural perspective (the intervention directive came from the Bank’s Financial Policy Committee, not the Monetary Policy Committee).

As Central Banking reported:

A problem for the BoE was that despite the unique features of the facility, it looked a lot like QE. It was widely referred to as such in the press and among investors. The BoE quickly disabused markets of the notion that it would buy at any price. But the perception remained that the central bank would struggle to exit from the support programme if market dysfunction continued.

Operation Twist, but for Market Stability

The pension/LDI leverage squeeze that the BoE was addressing was located in long-dated gilts. Indeed, the BoE’s purchase program targeted gilts with more than 20 years to maturity. (And inflation-linked gilts: it later added all inflation-linked gilts with maturities of at least 3 years. It bought about £12B of long-dated gilts and £7B of inflation-linked gilts.)

However, the BoE had previously outlined that its planned QT program would “be distributed evenly across short, medium and long maturity sectors. These sectors are defined as: gilts with a residual maturity of between 3-7 years (short), those with a residual maturity of between 7-20 years (medium), and those with a residual maturity of over 20 years (long).”

Thus, it’s not clear that halting QT altogether was needed or appropriate. Would continuing to sell 7-year bonds have diminished the effectiveness of BoE’s pension-driven intervention? Seems unlikely.

The Fed (and other central banks), should thus think about communicating an Operation Twist of sorts. It will need to be relatively flexible (er, vague), given its uncertain where along the yield curve the “break” might occur in the event it does. But the Fed can commit to leaving QT on autopilot while also stepping in to specific segments of the market as necessary to contain any fire sale dynamics like those seen at the long end of the gilt market. This retains everything the BoE did right, while potentially limiting any downside impact on the credibility of the Fed’s hawkish crusade against inflation.

The Fed can leave this plan under glass until (if!) a Treasury market break actually materializes. But also, to the extent the Fed communicates a willingness to execute such a strategy in advance of any market breakage (which of course comes with its own, moral-hazard-y drawbacks), it may increase the Fed’s hawkish credibility.

With such advance communication, the Fed could also consider committing to sterilizing any interventions. That is, if it does its $60B of QT and has to intervene for—for sake of example—$5B of 10ish-year Treasuries, it could offset these buys with more sales elsewhere along the yield curve. Further hawkish credibility.

Advance communication could also help at least reduce the likelihood that a breakage occurs—to the extent it moves the needle on market participants’ willingness to intervene before the Fed actually opens its balance sheet. As we saw with the relatively small purchase amount from the BoE, the communication of a willingness to intervene can do much of the heavy lifting, even if it occurs after the market break has.

A broad commitment to intervene as necessary to address any undue Treasury market ructions could help the Fed’s ongoing QT campaign achieve the ideal of being “like watching paint dry.”

Comments are turned off here but more than welcome via email (steven.kelly@yale.edu) and Twitter (@StevenKelly49).